“It’s Not You, It’s The Room”— Are The High-Tech, Active .

RESEARCHANDTEACHING“It’s Not You, It’s the Room”—Are the High-Tech, Active LearningClassrooms Worth It?By Sehoya Cotner, Jessica Loper, J. D. Walker, and D. Christopher BrooksSeveral institutions have redesignedtraditional learning spaces to betterrealize the potential of active,experiential learning. We comparestudent performance in traditionaland active learning classroomsin a large, introductory biologycourse using the same syllabus,course goals, exams, and instructor.Using ACT scores as predictive,we found that students in the activelearning classroom outperformedexpectations, whereas those in thetraditional classroom did not. Byreplicating initial work, our resultsprovide empirical confirmationthat new, technology-enhancedlearning environments positivelyand independently affect studentlearning. Our data suggest thatcreating space for active learningcan improve student performancein science courses. However, werecognize that such a commitmentof resources is impractical formany institutions, and we offerrecommendations for applying whatwe have learned to more traditionalspaces.82Journal of College Science TeachingAmong active learning strategies, team-based learning(or cooperative learning)has perhaps the longesthistory and the richest evidentiarybasis (Michael, 2006; Prince, 2004;Springer, Stanne, & Donovan, 1999).Yet architecturally, traditional classrooms with rows of students facinga single focal point—the instructoror a central screen or board—are notnecessarily conducive to peer interaction (Milne, 2006; Oblinger, 2006).In response to this perceived barrierto the implementation of active learning strategies, a few institutions havepioneered the reconfiguration of entire classrooms (e.g., North CarolinaState University’s SCALE-UP classrooms [Beichner et al., 2007] and theTEAL project at MIT [Dori, 2007]).These rooms are designed to encourage student interaction and facilitateactive or team-based collaborativelearning by including features such asround tables, movable chairs, studentlaptop connections for sharing workon overhead projectors, and tablesidewhiteboards.Some work has been done to assess the effectiveness of these roomsin contributing to meaningful studentinteractions and in increasing studentunderstanding of course material (Dori& Belcher, 2005; Gaffney, Richards,Kustusch, Ding, & Beichner, 2008).At both North Carolina State University and MIT, students in the modifiedclassrooms had lower failure ratesand increased levels of conceptualunderstanding compared with studentstaking the course in a traditional classroom using a lecture-based approach.However, the interpretation of theseearly results is constrained because ofmethodological limitations; specifically, the previous work lacks sufficientcontrols to make a case for the physicalspace as opposed to the instructor (orpedagogical approach) in contributingto student gains.After a pilot study of two activelearning classrooms (or ALCs), theUniversity of Minnesota constructedthe new Science Teaching and StudentServices (STSS) building with 10ALCs (Whiteside, Brooks, & Walker,2010). These classrooms, modeled inpart on North Carolina State University’s SCALE-UP classrooms, consistof a centralized teaching station withtechnological controls and from 3 to14 nine-person round tables, eachof which has several laptop connections, a dedicated large overhead LCDscreen, whiteboard space, severalmicrophones, and visual access tolarge projection screens (Figure 1).Constructing these rooms requireda significant up-front and long-termcommitment of scarce resources, expenditures that are especially onerousfor a public institution facing budgetconstraints and increased tuitioncosts in a strapped economy. Was theinvestment worth it?

Learning gains inactive learningclassroomsTo determine whetherthe investment has hadthe desired effects, researchers at the University of Minnesota haveengaged in a longitudinal investigation of theALCs’ impact on howinstructors teach andhow students learn.Early work on theALCs (Whiteside et al.,2010) focused on studentand faculty attitudes,expectations, and perceptions of the rooms.Faculty members hadhigh expectations whenthey began teaching inthe ALCs and stronglypositive attitudes towardthe spaces at the end ofthe term; many notedthat their role changedin the ALCs, shiftingto the role of a learningcoach or facilitator. Students also had stronglypositive attitudes towardthe ALCs, particularlyregarding the rooms’ facilitation of teamworkand collaboration withtheir classmates and theability of ALCs to appealto a variety of learningstyles. Both faculty andstudents noted the importance of the round-tabledesign in altering theclassroom dynamic inimportant ways. However, some differencesemerged: Freshmen andsophomores rated therooms more highly thanFIGURE 1Top: Layout of traditional classroom (STSS 220). Bottom: Layout of active learningclassroom (STSS 330). More details available at http://www.classroom.umn.edu/.Vol. 42, No. 6, 201383

researchandteachingdid upperclassmen, and metropolitanstudents perceived the rooms as moreuseful than did students from ruralbackgrounds.Preliminary studyFollowing initial work on perceptions and attitudes, researchersworked with a faculty member todesign a quasi-experimental studyin an effort to isolate the impactof the room itself on student learning. The instructor taught the samesection of an introductory biologycourse (Postsecondary Teachingand Learning 1131), but in two different rooms—an ALC and a traditional classroom. The two sectionswere taught at the same time of day,yet on different days of the week.Course materials, assignments, exams, and pedagogical approacheswere controlled across sections; theonly factor that varied systematically was the room itself. Researchers were unable to assign studentsrandomly to the treatment and experimental sections; however, students were unaware of the room differences during course registration,allowing for post hoc demographicequivalency to be established. Theonly anomaly that emerged betweenthe sections was that students in thetraditional classroom had, on average, significantly higher ACT scoresTABLE 1Students in the traditional classroom had significantly higher ACTscores (yet did not perform significantly better in the course).Traditional 1020.65Sex (female )1640.78(0.04)1020.04Year (senior 4;first year .04)1070.66(0.06)740.09ACT score26.36(0.31)13925.32(0.37)811.04*Grade (% of total)77.77(0.69)16176.69(0.84)1021.28Note: Cell entries for each classroom are means, standard errors (in parentheses),and the number of cases for two-group, mean-comparison tests. ALC activelearning classroom.*p .05.84Journal of College Science Teachingthan did students in the ALC (22.54vs. 20.52; p .05). Given the predictive nature of ACT scores (e.g.,ACT, 2007; Marsh, Vandehey, &Diekhoff, 2008; Stumpf & Stanley,2002), we expected students in thetraditional classroom to earn highergrades than their peers in the ALC.However, at the end of the term,there was no significant differencein class performance, on identicalmetrics, between the two sections(Brooks, 2011). This finding suggested that the ALCs positively affected student learning.Methods and data collectionIn spring 2011, we sought to replicate these initial results using asimilar quasi-experimental designwith a different course, different instructor, and groups of students thatwere both larger and more representative of our general student population than the students involved inthe initial study. Specifically, oneinstructor worked with two groupsof students enrolled in an introductory biology course for nonsciencemajors (Biology 1003). One groupmet in a traditional classroom, theother in an ALC. In addition to controlling for instructor, every attemptwas made to keep course materialand designed activities the sameacross the two sections. Laboratoryexercises were identical, as werequizzes, homework assignments,and all three major exams.Biology 1003 is a large introductory class (N 161 and 102 for thetraditional and active sections, respectively). Survey data were collected viasurveys administered in class on thelast day of the term. The Universityof Minnesota’s Institutional ReviewBoard approved the protocol, andwe obtained informed consent forall subjects. Demographic and grade

data were supplied by the UniversityOffice of Institutional Research andthe instructor, respectively.A project PI and a trained studentresearcher collected observationaldata on 50% of randomly selectedclass periods for both sections. Anobserver recorded the levels at whichstudents appeared to be “on task,” aswell as specific characteristic behaviors of the instructor (e.g., lecturing,consulting individuals or groups, andworking problems with the documentscanner) and the students (e.g., consulting in a group, asking questions,and working on a group activity).And finally, students were surveyedabout their experiences and perceptions in their respective classroomson the last day of class. The designwas intentionally quasi-experimentalin that we used principles of experimental design, but we were unable torandomly assign subjects to controland experimental groups. However,we worked with the same instructor, same syllabus, and same testitems, and the sections were offeredback-to-back in the late morning onthe same days (Tuesdays and Thursdays); only the space was allowedto vary systematically. Although therandom assignment of students intosections that would have afforded afully experimental design was notpossible, the enrollment process (e.g.,registering for a specific lab section),coupled with post hoc equivalencytests, essentially approximates randomization. We suspect dialoguebetween the sections was minimal tononexistent: Students enrolled froma variety of majors within a verylarge university, lab sections werespecific to each class section, andthe sections—although offered backto-back—were on different floors ofthe classroom building with only 15minutes separating them.FIGURE 2Expected versus actual grades (BIOL 1003). Students in the ALC earnedsignificantly higher final grades than their ACT scores predicted (****p .0001).All instruments used in this research have been tested for scale reliability and validity and are availableonline at http://z.umn.edu/lsr.ResultsLike our earlier study, students in thetraditional classroom had, on average, significantly higher ACT scoresand were thus expected to outperformstudents in the ALC. And, like ourearlier study, final scores—on identical metrics—were not significantlydifferent across sections (Table 1).Given what we know about the predictive capacity of the ACT scoresfor grades, this finding is surprising.Using a point estimation regressionmodel, we expected students in theALC to earn approximately 6 percentage points lower on their finalgrades than their peers in the traditional classroom; instead, students inthe ALC earned half of a letter grademore than expected (p .0001; Figure 2). However, just as we observedin the first experiment (Brooks,2011), the altered environment didnot undermine the ACT’s predictivepower. In both classrooms, the ACTscore served as a reliable predictorof performance, predicting 20% and23% of variation in student grades inthe traditional and ALC spaces, respectively (Table 2, Model 1). Evenwhen we control for a host of demographic variables, ACT compositescores continued to be the only significant predictor of student gradeswith little explanatory improvementover the initial model (Table 2, Models 2 and 3). Thus, the patterns of evidence in support of our initial findings—that ALCs have a significantand independent impact on studentperformance—are identical.In the ALC, the same instructor,teaching the same material, spentVol. 42, No. 6, 201385

researchandteachingmore time consulting and leadinggroup activities and less time at thepodium (Figure 3). Furthermore, tetrachoric correlational analysis (rho)reveals significant and positive relationships between ALCs and groupactivities (p .05) and consultation (p .01), and negative relationships withlocation in the room (p .05).Several significant differencesemerged in student perceptions of thelearning spaces (Figure 4): Studentsin the ALC reported a higher level ofengagement than did their peers inthe traditional classroom (p .0001);also, ALC students reported higherroom flexibility in regard to in-classactivities (p .001); finally, studentsin the ALC perceived a higher alignment between the room and the course(p .01).DiscussionHow can a classroom positivelyOur findings show that students in affect student learning?the ALC outperformed their counterparts in the traditional classroom,everything else being equal (gender,race, year in school, etc.). By replicating initial work, our results provideempirical confirmation that new andtechnology-enhanced learning environments positively and independently affect student learning.We are doubly intrigued by thefact that these effects were noted inthe courses of two very different, butskilled and experienced, instructors—one a faculty member using a hybridlecture problem-solving approachin both classrooms and one a facultymember using active-lecturing techniques with both groups (the presentstudy).Model 1Model 2Model 3Model 1Model 2Model 2.53)2.77(2.33)1.21(2.85)Work on learning spaces encouragesus to reevaluate the role of a physical space in facilitating or hinderingthe construction of knowledge (Whiteside et al., 2010). Specifically, traditional classrooms, especially thosewith chairs bolted in place, emphasize the instructor over the studentand make group formation seem awkward and contrived. Round tables allow students “face time” with otherstudents, deemphasize the role of theinstructor, and permit groups to formnaturally. We tested these predictionsvia a systematic analysis of studentand instructor behaviors, throughoutthe course of a class session, in 15randomly selected sessions during thesemester.Our analysis of classroom behaviorshighlights some possible causes for theroom effect (Figure 3). Specifically, inspite of concerted effects to maintainequivalency across the two sections,the space itself appears to have exacted behavioral differences in coursedelivery. Student survey responsesreinforce this notion (Figure 4). Weacknowledge that positive studentperceptions of the impact of the roomare not the same as saying the roomactually has an impact. Regardless,these data are consistent with the behavioral differences and performancegains documented .19)0.75(1.78)Was the investment worth it?TABLE 2Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression of ACT score on course grade,by section.Traditional 45)Adjusted R20.200.240.260.230.230.22N13913997818158Note: Cell entries are unstandardized OLS regression coefficients with standard errorsin parentheses. ALC active learning classroom.*p .05. **p .01. ***p .001.86Journal of College Science TeachingWe believe that the investment inALCs at the University of Minnesotawas worth it. Documented increasesin student engagement and confirmedaverage gains of nearly 5 percentagepoints in final grades are improvements in the student academic experience that few educational interventions could aspire to. However,whether these improvements warrant

the capital investment in ALCs is ajudgment each educational institutionmust make for itself, drawing on localpriorities and resources.Instructors may need to think seriously and creatively about changingthe manner in which they deliver theircourses in spaces such as these—notonly for the sake of navigating thechallenges of teaching in a decenteredspace, but also to take advantage ofthe features of the room that allow usto better realize the benefits of activelearning. The classroom architecture isbound to frustrate the efforts of facultywho don’t yield to the rooms’ noveldemands. There is no well-identified“stage” from which to deliver a traditional lecture. Half of the students inthe class may be facing away from theinstructor at any given time. Teacherswho view silence as engagement willneed to adjust their perceptions, asone goal of decentralized classroomsis increased small-group interactionand this activity can be noisy and difficult to monitor. And, in the case ofthe ALCs at our institution, there isa learning curve with respect to thetechnological capabilities of the rooms.Considering these hurdles, a substantial commitment to the ALC isrequired from instructional staff. Asevidence of this commitment, a variety of institutional resources existat the University of Minnesota to aidfaculty in the transition to these novellearning spaces. Resources range fromtechnology training courses, to monthlong workshops, to 18-month facultydevelopment programs—all designedto support technology-enhanced learning. A faculty-development programexplicitly focused on ALCs would bea welcome addition to this arsenal.Given the resources expended inmaking this transformation, facultyshould require evidence of the ALCs’effectiveness. In addition to the exist-ing work on student engagement viaactive learning, the results describedherein document the positive impactsof designing spaces for active learning.Recognizing that such a commitment of resources is impractical formany institutions, we offer recommendations for applying what we’velearned to more traditional spaces.Figures 3 and 4 suggest that the benefits of these rooms may hinge on theirflexibility and their explicit emphasison small-group interaction (e.g., theround, nine-person tables). Namely,any efforts to decentralize the room,with an overt focus on group dialogue,are likely to increase the individualstudent’s sense of accountability andlead to the learning gains that resultfrom peer interaction. Decentralizationcan be accomplished several ways,from something as simple as movablechairs, to small tables with whiteboards for impromptu problem-solvingor presentation, to full-blown ALCs asdocumented previously. When a student enters one of our ALCs for the firsttime, he or she gets a clear messagethat this class will not be “businessas usual.” However, we are confidentthat this message, and the gains weassociate with ALCs, can be achievedin numerous ways by inspired facultyseeking the best for their students. nAcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the generousfinancial and time commitments of theFaculty Fellows Program in the Office ofInformation Technology at the Universityof Minnesota. We thank the BiologyProgram for additional support, and ofcourse we are forever indebted to ourstudents.FIGURE 3Interval frequency of observed classroom activity and instructorbehavior (BIOL 1003): traditional vs. ALC. Data are percentages of5-minute intervals in which the activity or behavior was observed.Given that more than one activity or behavior was possible in any giveninterval, totals do not sum to 100%. *p .05. **p .01. ***p .001.Vol. 42, No. 6, 201387

researchandteachingReferencesACT. (2007). The ACT technical manual.Iowa City, IA: Author.Beichner, R. J., Saul, J. M., Abbott, D.S., Morse, J. J., Deardorff, D. L.,Allain, R. J., . . . Risley, J. S. (2007).Student-centered activities for largeenrollment undergraduate programs(SCALE-UP) project. In E. F. Redish& P. J. Cooney (Eds.), Researchbased reform of university physics(pp. 2–42). College Park, MD:American Association of PhysicsTeachers.Brooks

“It’s Not You, It’s the Room”— Are the High-Tech, Active Learning Classrooms Worth It? By Sehoya Cotner, Jessica Loper, J. D. Walker, and D. Christopher Brooks Several institutions have redesigned traditional learning spaces to better realize the potential of active, experiential learning. We compare student performance in traditional

Independent Personal Pronouns Personal Pronouns in Hebrew Person, Gender, Number Singular Person, Gender, Number Plural 3ms (he, it) א ִוה 3mp (they) Sֵה ,הַָּ֫ ֵה 3fs (she, it) א O ה 3fp (they) Uֵה , הַָּ֫ ֵה 2ms (you) הָּ תַא2mp (you all) Sֶּ תַא 2fs (you) ְ תַא 2fp (you

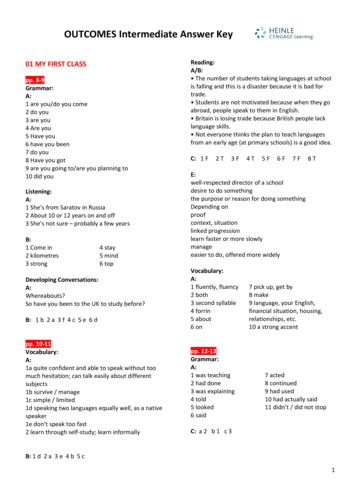

OUTCOMES Intermediate Answer Key 01 MY FIRST CLASS pp. 8-9 Grammar: A: 1 are you/do you come . 2 do you . 3 are you . 4 Are you . 5 Have you . 6 have you been . 7 do you . 8 Have you got . 9 are you going to/are you planning to . 10 did you . Listening: A: 1 She’s from Saratov in Russia . 2 About 10 or 12 years on and off . 3 She’s not sure .

Jan 09, 2022 · for I have redeemed you; I have called you by name, you are mine. When you pass through the waters, I will be with you; and through the rivers, they shall not overwhelm you; when you walk through fire you shall not be burned, and the flame shall not consume you. For I am

teach you prayer. Prayer opens hearts and gives hope, and faith is born and strengthened. Little children, with love I am calling you: return to God, because God is love and your hope. You do not have a future if you do not decide for God; and that is why I am with you to guide you to decide for conversion and life, and not for death. Thank you for

but you’d never say this to my face. Being proud doesn’t change that you’re a coward. I will not defend you when you attack me and you can’t undo your own doing. One day this will haunt you, come back to you, You can’t hide forever you know. You’ll have to show yourself one day and when you

ask you to swear or affirm that you will tell the truth in your testimony. v. You will offer testimony. If you have a representative, he or she will usually ask you questions relevant to your appeal. If not, you should tell the Veterans Law Judge why you believe you deserve the benefits you are seeking. v. You may submit more evidence. If you .

Lord, You’ve been so good to me Lord, I thank You You are my help, You meet my need Lord, I thank You You were my strength when I was weak Lord, I thank You Your love and mercy rescued me Lord, I thank You I thank You Lord Lord, I thank You I thank You Lord Lord, I thank You Every time I think of

Dear friend, I want you to know I see you. I value you. I stand behind you and beside you. This world is not easy. This world is hard. But it is also filled with beauty and love – and these are the things I wish for you. I want you to know that you are loved, that you are the beauty we crave so much. You ma