Low Carbon Jobs - D2e1qxpsswcpgz.cloudfront

A report for UKERC byUKERC Technology & Policy Assessment FunctionLow carbon jobs:The evidence for net job creation frompolicy support for energy efficiency andrenewable energy

2Low carbon jobs:The evidence for net job creation frompolicy support for energy efficiency andrenewable energyA report by the UKERC Technology & PolicyAssessment FunctionWill BlythRob GrossJamie SpeirsSteve SorrellJack NichollsAlex DorganNick HughesNovember 2014 v. 2REF UKERC/RR/TPA/2014/002www.ukerc.ac.ukFollow us on Twitter @UKERCHQ

Low carbon jobs: The evidence for net job creation from policysupport for energy efficiency and renewable energy1PrefaceThis report was produced by theUK Energy Research Centre’s(UKERC) Technology and PolicyAssessment (TPA) function.The TPA was set up to inform decision-making processesand address key controversies in the energy field. Itaims to provide authoritative and accessible reportsthat set very high standards for rigour and transparency.The subject of this report was chosen after extensiveconsultation with energy sector stakeholders and uponthe recommendation of the TPA Advisory Group, whichis comprised of independent experts from government,academia and the private sector.The primary objective of the TPA, reflected in this report,is to provide a thorough review of the current state ofknowledge. New research, such as modelling or primarydata gathering may be carried out when essential. It alsoaims to explain its findings in a way that is accessible tonon-technical readers and is useful to policymakers.The TPA uses protocols based upon best practice inevidence-based policy, and UKERC undertook systematicand targeted searches for reports and papers related tothis report’s key question. Experts and stakeholders wereinvited to comment and contribute through an expertgroup. The project scoping note and related materials areavailable from the UKERC website, together with moredetails about the TPA and UKERC.About UKERCThe UK Energy Research Centre is the focal point for UKresearch on sustainable energy. It takes a whole systemsapproach to energy research, drawing on engineering,economics and the physical, environmental and socialsciences.The Centre’s role is to promote cohesion within the overallUK energy research effort. It acts as a bridge betweenthe UK energy research community and the wider world,including business, policymakers and the internationalenergy research community and is the centrepiece of theResearch Councils Energy Programme.www.ukerc.ac.uk

2Executive SummaryIntroductionCounterfactuals‘Green’ sectors account for as many as 3.4 million jobsin the EU, or 1.7% of all paid employment, more than carmanufacturing or pharmaceuticals. Given the size of thegreen jobs market, and the expectation of rapid changeand growth, there is a pressing need to independentlyanalyse labour market dynamics and skills requirementsin these sectors. What is more controversial is thequestion of whether policy driven expansion of specificgreen sectors actually creates jobs, particularly when thepolicies in question require subsidies that are paid forthrough bills or taxes. There are strong views on bothsides of this debate. Politicians often cite employmentbenefits as part of the justification for investing in cleanenergy projects such as renewables and energy efficiency.Such claims are often backed up by project or sectorspecific analyses. However, other literature is moresceptical, claiming that any intervention that raises costsin the energy sector will have an adverse impact on theeconomy as a whole.In the case of electricity generation, where new sources ofsupply may be needed in order to meet growing demand,the calculation of net employment impacts needs to takeaccount of counterfactuals – i.e. what other kind of powergeneration sources would have been built instead if thecountry were not following a green policy pathway? Themost optimistic assessments of green job impacts tend toexclude consideration of counterfactuals, counting onlythe jobs directly attributable to the project concerned.The UKERC Technology and Policy Assessment (TPA)theme was set up to address such controversies throughcomprehensive assessment of the current evidence. Thisreport aims to answer the following question:“What is the evidence that policy support forinvestment in renewable energy and energyefficiency leads to net job creation in theimplementing regions?”The focus on net jobs here is important: whilst it is clearthat jobs can be created at a local scale by spendingmoney on new infrastructure projects, other jobs may bedisplaced if the new project provides activities or servicesthat would otherwise have been provided elsewhere inthe economy. Analysis of net jobs therefore needs to takeaccount of both jobs created and jobs displaced.On the other hand, some of the most sceptical literature isbased on a rather aggressive definition of counterfactualwhich compares green energy investments with the mostlabour-intensive sector in the economy (e.g. construction)on the basis that if economic stimulus were the solejustification of policy, then interventions should befocussed on sectors with the highest employment impactper pound invested. However, assuming that policy-driveninvestment could flow unrestricted between very differentsectors in this way, does not seem realistic in the UKcontext. Here, electricity policy options tend to be basedon influencing companies’ investment decisions regardingtheir choice of technology to meet a particular level ofgeneration capacity.For the purposes of this study, the counterfactual istherefore defined within the electricity sector only. Wecompare the jobs impact of investing in renewablesand energy efficiency with the jobs impact of investingin an equivalent amount of fossil-fuel plant. For thisstudy, we convert different types of job (e.g. short-termmanufacturing and construction jobs and long-termoperation and maintenance jobs) to a single measure offull-time long term job equivalents. In order to measurelabour intensity, we calculate an indicator of jobs perannual GWh produced – this compares generation sourceson a like-for-like basis in terms of their physical scale.We also compare job intensity figures for short-term jobimpacts, which may be particularly relevant for assessingthe potential for economic stimulus interventions.

Low carbon jobs: The evidence for net job creation from policysupport for energy efficiency and renewable energyModelling employment impactsThe methodologies used in the literature to estimatejob impacts are reviewed. Primary data is often gatheredthrough case studies, together with questionnaires andsupply-chain surveys. Studies often include not just directemployment impacts, but also the wider ripple-throughindirect effects of increased demand in the supply chain,as well as the induced effect of higher spending potentialfor those households that have benefitted from the higheremployment rates. The most common analytical approachfor these wider effects is input-output modelling. Studiesalso address wider macro-economic impacts throughcomputable general equilibrium (CGE) modelling, ormacro-econometric approaches. The pros and cons ofeach approach are reviewed in the report.The quantitative evidence base comes from two maindifferent types of literature. The first (comprising themajority of the literature surveyed) are studies whereauthors provide estimates of gross job impacts ofindividual projects for specific types of generation. Toget an approximate estimate of net job impacts, we thencompare across different studies the gross job impacts ofinvesting in renewable energy and energy efficiency withthe gross job impacts of investing in fossil fuel plant. Inthe second type of literature, authors explicitly calculatethe net job impacts of renewables and energy efficiencycompared to fossil fuels, giving us a direct indicationof the net impacts. This was a smaller set of literature,but produced a roughly similar result to the first set ofliterature, giving some additional confidence in the overallconclusion.The evidence on job creationBased on a systematic review of this literature, there is areasonable degree of evidence that in general, renewableenergy and energy efficiency are more labour-intensivein terms of electricity produced than either coal- orgas-fired power plant. This implies that at least in theshort-term, building new renewable generation capacityor investing in greater energy efficiency to avoid the needfor new generation would create more jobs than investingin an equivalent level of fossil fuel-fired generation. Themagnitude of the difference is of the order of 1 job perannual GWh produced.To put this into perspective, total electricity supply in theUK is around 375,000 GWh, whilst total employment (fulltime and part-time) in the UK electricity sector as a wholeis 136,000 , putting the average employment intensity forthe sector as a whole at around 0.4 jobs/annual GWh. Amarginal increase in labour intensity of 1 job per annualGWh implied by a shift from fossil fuels to renewablesor energy efficiency is therefore substantial. There areconsiderable variations between technologies, with windpower appearing to be relatively less labour-intensive,whilst solar and energy efficiency investments appearmore labour-intensive.3Whilst the evidence seems reasonably robust thatrenewables and energy efficiency are in generalmore labour-intensive than fossil fuels, this does notautomatically mean that preferential investment inthese technologies will lead to higher employment in theeconomy as a whole. Short-term employment impactsof diverting investment from fossil fuel generation torenewables and energy efficiency may very well bepositive. However, long-term impacts will depend on howthese investments ripple through the economy, and inparticular the impact on disposable household incomes.Macroeconomic conditionsThe answer to this question depends very much onmacroeconomic conditions. In a depressed economy inwhich aggregate demand is low compared to potentialsupply of goods and services (creating a so-called ‘outputgap’), then Keynesian measures of stimulating additionalemployment in particular sectors are very likely to lead tohigher overall employment, and it makes sense to focussuch efforts on more labour-intensive options. On theother hand, in an economy which is closer to ‘equilibrium’conditions, with close to ‘full employment’, the room forsuch manoeuvres is more limited, and government-ledinvestments may crowd out private investment leading tolower-than-expected net employment results.Fiscal and monetary stimuli therefore have a role toplay during periods of recession, but can do more harmthan good during periods of full employment. Goodpolicy design is therefore a matter of timing. However,estimating the duration and depth of a particular periodof recession is far from an exact science. Lags in theeffects of policy can exacerbate the difficulties. Resultsfrom the few studies that have used computable generalequilibrium models, reflect this dichotomy.Some studies indicate a negative employment impactof renewables, while others indicate a positive impact,the differences largely reflecting the authors’ a prioriassumptions regarding these pivotal macroeconomicissues. The more nuanced studies show positiveemployment impacts in the short-run due to the higherjob intensity, with negative effects later on as price effectsfeed into economic behaviour. However, none of thestudies reviewed factored in any externalities of fossil fuelplant, such as environmental impacts or energy securityconsiderations.Policies that have impacts beyond the time horizon ofthe current business cycle lock-in the economy to aparticular set of behaviours that go beyond their initialstimulus impacts. This is particularly true for decisions inthe electricity sector which concern long-lived strategicinfrastructure. In these cases, it is important to assess thebalance of costs and benefits to the economy in terms ofthe impact on growth potential. When designing stimulusprogrammes, it makes sense to support technologiesand projects that support technological progress in the

4long-term, because if they have a persistent impact onthe economy beyond the timeframe of the direct stimuluseffects, they should also help contribute to long-termgrowth. In this longer-term context, labour intensity is notin itself economically advantageous, as it implies lowerlevels of labour productivity (economic output per worker),which could adversely impact prospects for economicgrowth.Therefore, the employment characteristics that matterin the long-run are not how many jobs are created perunit of investment, but whether or not the investmentcontributes to an economically efficient transitiontowards the country’s strategic goals, taking account ofexternalities such as environmental impacts and energysecurity considerations.ConclusionsIn conclusion, there is reasonable evidence from theliterature that renewables and energy efficiency are morelabour-intensive than fossil-fired generation, both interms of short-term construction phase jobs, and in termsof average plant lifetime jobs. Therefore, if investment innew power generation is needed, renewables and energyefficiency can contribute to short-term job creation solong as the economy is experiencing an output gap, suchas is the case during and shortly after recession.In the long-term, if the economy is expected to return tofull employment, then ‘job creation’ is not a meaningfulconcept. In this context, high labour intensity is notin itself a desirable quality, and ‘green jobs’ is not aparticularly useful prism through which to view thebenefits of renewable energy and energy efficiencyinvestment. What matters in the long-term is overalleconomic efficiency, taking into account environmentalexternalities, the desired structure of the economy, andthe dynamics of technology development pathways. Inother words, the proper domain for the debate about thelong-term role of renewable energy and energy efficiencyis the wider framework of energy and environmentalpolicy, not a narrow analysis of green job impacts.

Low carbon jobs: The evidence for net job creation from policysupport for energy efficiency and renewable energy5ContentsExecutive Summary021Introduction082Key concepts112.1 What are Green Jobs, and How can we Measure Them?122.2 Macroeconomic Perspectives and Concepts19323Modelling methodologies3.1 Input-Output Models243.2 Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) analysis273.3 Macroeconometric models29431Comparative Analysis of Job Estimates from the Literature4.1 Methodology324.2 Gross Jobs Summary334.3 Net Jobs Summary374.4 Breakdown by Technology394.5 General Equilibrium Studies475Summary & Conclusions51References54Appendix59A: How the Review was Conducted59B:Publications from the review that provided quantitative estimates of employment impacts61C:Expert Group, Peer Reviewers and acknowledgements66

6FiguresFigure 1Direct employment in EU wind sector by type of company surveyed14Figure 2Schematic showing the relationship between different types of job impact14Figure 3Job breakdown between manufacturing, installation and O&M17Figure 4The Output Gap – OECD Labour Market Outlook 201320Figure 5Schematic layout of an (analytical) Input-Output table24Figure 6Gross jobs per annual GWh generated34Figure 7Gross jobs per m invested35Figure 8Short-term direct jobs during the construction phase of projects36Figure 9Net jobs per annual GWh generated37Figure 10Net jobs per m invested38Figure 11Employment effects difference between RE and reference scenario39Figure 12Average results from individual publications; Wind39Figure 13Sensitivity ranges from individual publications; Wind40Figure 14Average results from individual publications; Solar41Figure 15Sensitivity ranges from individual publications; Solar42Figure 16Average results from individual publications; Other RE42Figure 17Sensitivity ranges from individual publications; Other RE43Figure 18Breakdown of job impacts by sector for biomass44Figure 19Average results from individual publications; Energy Efficiency44Figure 20Sensitivity ranges from individual publications; Energy Efficiency45Figure 21Average results from individual publications; Fossil Fuels46Figure 22Sensitivity ranges from individual publications; Fossil Fuels47Figure 23Importance of the source of financing on employment and welfare49

Low carbon jobs: The evidence for net job creation from policysupport for energy efficiency and renewable energyList of abbreviations andacronymsCCGTCombined Cycle Gas TurbineCCSCarbon Capture and StorageCESConstant Elasticity of SubstitutionCSPConcentrated Solar PowerDECCDepartment of Energy and Climate ChangeDSGEDynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (model)DSMDemand-Side ManagementEEEnergy EfficiencyESCOEnergy Service CompaniesEUEuropean UnionFTEFull Time Equivalent (jobs)GBPBritish Pounds ( )GWhGigawatt hourIOInput Output (tables)MRIOMulti-Regional Input-Output (tables)MWMegawattMWpMegawatt peakO&MOperations and MaintenanceOECDOrganisation for Economic Cooperation and DevelopmentPVPhotovoltaicsRERenewable EnergyRGGIRegional Greenhouse Gas InitiativeSAMSocial Accounting MatrixTPATechnology and Policy Assessment (a function of the UKERC)UKUnited KingdomUSUnited States of AmericaUKERCUK Energy Research CentreVARVector AutoRegression7

8Introduction1

Low carbon jobs: The evidence for net job creation from policysupport for energy efficiency and renewable energyWhy study green jobs? At one level, the answer is obvious.According to some estimates, green jobs already accountfor 3.4 million jobs in Europe (Rademaekers et al., 2012),more than in car manufacturing or the pharmaceuticalsindustry. If one accepts the need for ‘greening’ theeconomy, then the impacts of such a transition on thelabour market will clearly need to be understood. Inparticular, if the new ‘green’ sectors are to grow rapidly,there needs to be a sufficient skills base and industrialcapacity to facilitate this growth.During the boom in wind power in the late 2000s, forexample, there was evidence of a shortage of suitablyqualified engineers and maintenance staff across Europeto sustain the rapid growth of installations (Blanco andRodrigues, 2009). Other labour market impacts that needto be understood are the potential dislocations that mightoccur in the ‘losing’ sectors. These are important issues foreconomic and political analysis to investigate.However, there is a second and more contentious strandto the green jobs debate, which is the focus of thisreport. Are there, as some proponents claim (Pollin et al.,2009, UNEP, 2008, Bezdek, 2009), benefits to employmentfrom clean technologies that arise irrespective of theirenvironmental case? This claim is more controversial,with critics (Huntington, 2009, Morriss et al., 2009, Michaelsand Murphy, 2009) suggesting that the imposition ofmore expensive technologies will, overall, tend to beeconomically damaging. This report aims to investigatethe evidence on both sides of this debate.In some contexts (e.g. when measuring the size of thesector), it is important to explicitly define what is meantby a ‘green job’. Some categories of job will be obviously‘green’; installing and maintaining solar panels or windturbines, for example. Others are less obvious – are thelorry drivers who deliver the solar panels to site carryingout a green job? For the most part, these definitionalissues are of less concern in this report. The issue weaddress here is whether ‘green’ policies lead to thecreation of additional jobs. As long as the jobs contributeto fulfilling the aims of the policies, then they count asjob creation, irrespective of whether they individuallywould be considered as being particularly ‘green’. Tofurther avoid controversies around definitional issues,the report focuses on a relatively narrow subset of

‘Green’ sectors account for as many as 3.4 million jobs in the EU, or 1.7% of all paid employment, more than car manufacturing or pharmaceuticals. Given the size of the green jobs market, and the expectation of rapid change and growth, there is a pressing need to independently analyse labour market dynamics and skills requirements

These jobs include welders, pipe fitters and machine installers. Defining jobs 1. Direct jobs are jobs supported from direct project expenditure, such as jobs supported when a compressor is purchased for installation on site. 2. Indirect jobs are those which are supported from spending in the wider supply chain, such as those

hotel jobs, representing a gain of over 160,000 hotel jobs since 2015. The total number of US jobs supported by the hotel industry increased by 1.1 million since 2015 and represents more than 1-in-25 US jobs (4.2%). A representative hotel with 100 occupied rooms supports 241 total jobs, including 137 direct jobs and 104 indirect and induced jobs.

Amazon CloudFront Validation Checklist Detailed Description of Evidence Met Y/N 1.0 Case Study Requirements Each Customer Case Study includes the following details regarding Amazon CloudFront: Supporting information for the submitted case studies includes the following details: Amazon CloudFront use case, e.g., media and entertainment,

proposed hydrogen business model to overcome one of the key barriers to deploying low carbon hydrogen: the higher c ost of low carbon hydrogen compared to high carbon counterfactual fuels. The hydrogen business model is one of a range of government interventions intended to facilitate the deployment of low carbon hydrogen projects that will be

Podcast Discusses Carbon Cycle, Carbon Storage. The “No-Till Farmer Influencers & Innovators” podcast released an episode discussing the carbon cycle and why it is more complicated than the common perception of carbon storage. In addition, the episode covered the role carbon cycling can play in today’s carbon credits program.

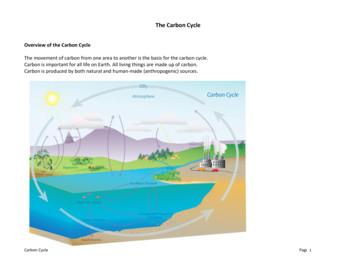

Carbon Cycle Page 1 The Carbon Cycle Overview of the Carbon Cycle The movement of carbon from one area to another is the basis for the carbon cycle. Carbon is important for all life on Earth. All living t

carbon footprint. The carbon footprint of a good or service is the total carbon dioxide (CO 2) and 1 Use of the Carbon Label logo, or other claims of conformance is restricted to those organisations that have achieved certification of their product’s carbon footprint by Carbon Trust Certi

THE GUIDE SPRING BREAK CAMPS 2O2O MARCH 16–27 AGES 5–13. 2 2020 Spring Break Camp Guide WELCOME Build Your COCA Camp Day 2 March 16–20 Camps 3–4 March 23–27 Camps 5–6 Camp Basics 7 Registration Form 8–9 Registration Guidelines/Policies 10 Summer’s coming early this year! Join us over Spring Break for unique and fun arts learning experiences. You’ll find favorites from .