Race And Ethnic Inequality In Educational Attainment In The United States

P1: GDZ0521849934c05.xmlCB844-Rutter0 521 84993 4February 4, 20055:255Race and Ethnic Inequality in EducationalAttainment in the United StatesCharles Hirschman and Jennifer C. LeeIntroductionIn the United States, as in other modern industrial societies, education isthe primary gateway to socioeconomic attainment. The single most important predictor of good jobs and high income is higher education. College graduates have average earnings 70 percent higher than those of highschool graduates (Day & Newburger, 2002). With such wide differencesin economic outcomes between the education haves and have-nots, mostresearch on economic inequality and the process of social stratificationmust begin with the determinants of schooling, and in particular, on thetransition from high school to college.Equality of opportunity, which lies at the heart of the American dreamof a meritocratic society, is still a distant goal. The fundamental, and inescapable, reality is that families work to subvert equality of opportunity.All parents, or at least most parents, want their children to do well andinvest considerable resources and time to sponsor, prod, push, and cajoletheir offspring. Parents provide economic and social support as well asencouragement to further their children’s schooling and subsequent occupational and economic attainment. Not all parents, however, have equalcapacity and ability in this role. Inequalities of wealth, income, and otherfamily resources certainly make a difference, and more subtle attributes,such as family cultures, child-rearing patterns, and social networks, mayalso influence the future career paths of children.Families are not the only influence on the educational and socioeconomic attainment of children. The availability and quality of schooling cansometimes create opportunities, even in the absence of family support. Forexample, the extraordinarily high level of high school graduation in theUnited Statesupwards of 85 to 90 percent of American adolescents graduate from high school (or receive a GED certification) is also a product of theavailability of free public high schools and laws requiring attendance in107Charles Hirschmanand Jennifer Lee. 2005. “Race and Ethnic Inequality in Educational Attainment in theUnited States.” In Michael Rutter and Marta Tienda, eds. Ethnicity and Causal Mechanisms, pp. 107-138.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress.

P1: GDZ0521849934c05.xml108CB844-Rutter0 521 84993 4February 4, 20055:25Charles Hirschman and Jennifer C. Leeschool until age 16. In addition, the existence of college tuition poses constraints, especially to those from lower socioeconomic background. Thus,although there is a perceived opportunity for all to attain postsecondaryeducation in the United States, those from a lower socioeconomic background are less able to afford it (Karen, 2002).Another important dimension of social stratification in the United Statesis race and ethnicity. The American fabled commitment to freedom ofopportunity for upward mobility has never been universal. AmericanIndians and African Americans were denied basic rights by law for muchof American history, and only in recent decades has there been the beginning of national efforts to right these historical injustices. Efforts to incorporate other minority groups, including immigrants from Europe, Asia,and Latin America (including those of Spanish heritage in annexed lands)have been uneven. There have been periods of hostility interspersed withindifference and occasional moments of welcome. The long-term progressof the descendants of immigrants is generally considered one of the greatachievements of American social democracy, though the process has beenslow, uneven, and incomplete.In this chapter, we analyze the historical and contemporary patterns ofrace and ethnic inequality in education in the United States. After reviewing some of the major theories of race and ethnic influences on educationalattainment, we describe some features of recent historical trends in educational attainment and transitions. The primary empirical focus of thisstudy is an inquiry into the socioeconomic sources of race and ethnic differentials in educational ambitions, and in particular, the college plans andapplications among high school seniors in a metropolitan school districtin the Pacific Northwest. Although race and ethnic educational disparitiesare somewhat less in this region than for the country as a whole, the underlying structure mirrors national patterns. Differences in family socioeconomic background explain a significant share of the underachievementof historically disadvantaged groups. Although Asian American familiesare quite heterogeneous, several national-origin groups have very higheducational ambitions even among families with modest socioeconomicresources.Theories of Ethnic Inequality in Educational AttainmentTheories of race and ethnic stratification stress the impact of poor socioeconomic origins and discrimination on the lower attainments of minority groups. These factors are particularly important in explaining thelower educational and socioeconomic achievement of African Americansin American society (Duncan, 1969; Lieberson, 1980; Walters, 2001). Forthe first six decades of the twentieth century, African Americans had to

P1: GDZ0521849934c05.xmlCB844-Rutter0 521 84993 4Ethnic Inequality in Educational AttainmentFebruary 4, 20055:25109confront state-sponsored segregation (including in public education) inthe South and de facto segregation and informal color bars throughout thecountry.Historically, other race and ethnic groups in the United States had alsobeen handicapped by poverty, residential segregation, and discrimination, but the magnitudes of each have generally been less than those encountered by African Americans. Hispanics (Mexicans, in particular) andAmerican Indians have had educational attainments even lower than thoseof African Americans (Mare, 1995). Asian Americans also experienced considerable political, social, and economic discrimination during the first halfof the twentieth century, but were able to make important educational gainseven under difficult circumstances (Hirschman & Wong, 1986). Immigrantsfrom southern and eastern Europe who arrived in the early decades of thetwentieth century started at the bottom of the urban labor market, buttheir children were able to reach educational and occupational parity withother White Americans by the middle decades of the twentieth century(Lieberson, 1980).There has been considerable socioeconomic progress for all racial andethnic groups during the second half of the twentieth century, but thepace of change has been much slower for Black Americans than for othergroups (Hirschman & Snipp, 1999; Jaynes & Williams, 1989). In particular,African Americans continue to experience extraordinarily high levels ofconcentrated poverty and residential segregation in major metropolitanareas (Massey & Denton, 1993) and encounter prejudice on a regular basis(Correspondents of The New York Times, 2001). During the same period,race relations have become more complex with the renewal of large-scaleimmigration from Asia and Latin America during the last three decades(Tienda, 1999; Zhou, 1997). Most of these new immigrants are non-White,including many Black immigrants from the Caribbean. The absorption ofthe new immigrants has been uneven, but there are signs that the childrenof many new immigrants are doing well in schools, even in very poorcircumstances (Caplan, Choy, & Whitmore, 1991; Waters, 1999; Zhou &Bankston, 1998).The classical sociological theory proposed to account for race and ethnicinequality has been the assimilation model, which suggests that forces ofmodern societies, such as industrialization, competitive labor markets, anddemocratic institutions, will gradually erode the role of ascriptive characteristics, including race and ethnicity, in social stratification (Treiman,1970). Although assimilation theory has many weaknesses, includingthe lack of a specific causal model and temporal boundaries, the theoryis largely consistent with the historical absorption of the children andgrandchildren of successive waves of immigration, largely from Europe,into American society (Alba & Nee, 1999).

P1: GDZ0521849934c05.xml110CB844-Rutter0 521 84993 4February 4, 20055:25Charles Hirschman and Jennifer C. LeeA more complex theoretical account of how and why the new immigrants and their children may follow rather different paths of incorporation into American society than did earlier waves of immigrants is the segmented assimilation hypothesis of Portes and Zhou (1993; also see Portes &Rumbaut 1996, 2001). Segmented assimilation implies a diversity of outcomes within and between contemporary immigrant streams. According tothe theory, some immigrant groups who have high levels of human capitaland who receive a favorable reception may be quickly launched on a path ofupward socioeconomic mobility and integration. Other groups with fewerresources may not be able to find stable employment or wages that allowthem to successfully sponsor the education and upward mobility of theirchildren. Indeed, the second generation may be exposed to the adolescentculture of inner city schools and communities that discourages educationand aspirations for social mobility (Gibson & Ogbu, 1991, Suarez-Orozco &Suarez-Orozco, 1995). A third path is one of limited assimilation, where immigrant parents seek to sponsor the educational success of their children,but limit their acculturation into American youth society by reinforcingtraditional cultural values.The segmented assimilation hypothesis provides a lens to understanding the discrepant research findings on the educational enrollment of recentimmigrants and the children of immigrants in the United States. Ratherthan expecting a similar process of successful adaptation with greaterexposure to (longer duration of residence in) American society, the segmented assimilation hypothesis predicts that adaptation is contingent ongeographical location, social class of family of origin, race, and place ofbirth (Hirschman, 2001). The segmented assimilation interpretation hasbeen supported by case studies of particular immigrant/ethnic populations that have been able to utilize community resources to pursue a strategy of encouraging the socioeconomic mobility of their children, but onlywith selective acculturation to American society.In their study of the Vietnamese community in New Orleans, Zhou andBankston (1998) report that children who were able to retain their mothertongue and traditional values were more successful in schooling than thosewho were more integrated into American society. This outcome is consistent with research that found that Sikh immigrant children were successfulprecisely because they were able to accommodate to the American educational environment without losing their ethnic identity and assimilatingto American society (Gibson, 1988). In another study, Mary Waters (1999)found that Caribbean immigrants are sometimes able to pass along an immigrant or ethnic identity to their children, which slows acculturation intothe African American community. These findings suggest that the apparent differences among assimilation theory, segmented assimilation theory,and other theories of race and ethnic inequality in educational attainment

P1: GDZ0521849934c05.xmlCB844-Rutter0 521 84993 4Ethnic Inequality in Educational AttainmentFebruary 4, 20055:25111may not be as great as suggested in some accounts. Socioeconomic originsand other attributes of families of origin are key explanatory variables inall theoretical perspectives.To explain racial/ethnic inequality in education, Ogbu (1978) arguesthat involuntary minority groups – that is, those who have a history ofoppression in the United States – are more likely to resist educational goalsin opposition to the values of dominant society. Voluntary minorities –those that freely migrate to the United States – have more optimism andare more likely to internalize mainstream values and goals. His argumenthas been questioned in recent studies that find that Black students havehigh educational aspirations, and their poorer school performance is dueto economic and social forces that limit the opportunities and materialconditions for them to realize these goals (Ainsworth-Darnell & Downey,1998).Many other aspects of social and cultural contexts may influence raceand ethnic difference in educational outcomes, including parenting stylesand socialization, peer group influences, and encouragement from significant others. For example, because of their concentration in segregatedinner-city schools, African American and immigrant children are mostlikely to encounter students and teachers with very low expectations forstudent attainment. Ferguson (1998) finds that teachers have lower expectations for Blacks than Whites and these perceptions have greater impacton Blacks than on Whites. In addition, Goyette and Xie (1999) argue that asocioeconomic explanation educational achievement is not adequate. Theyfind that for some Asian groups that are well assimilated, socioeconomicfactors play an important role, but not for others. However, for all groups,parental expectations are important factors in shaping educational expectations. Investigation of these topics is part of the future agenda of ourresearch.In this study, we present baseline models of the effects of family socioeconomic background and other social origin variables on plans for postsecondary schooling. We examine two dimensions of plans for college:one attitudinal and one behavioral. The attitudinal measure is plans forcontinued schooling right after high school, and the behavioral measureis whether the high school senior has actually completed an applicationfor college. Neither of these measures may perfectly predict future educational careers. Some students may be overly optimistic and not be awareof potential academic and economic obstacles that lie ahead. On the otherhand, some students may take a few years after high school to discovertheir latent educational ambitions and to begin college. Nonetheless, thedisparities in planning for college among high school seniors provide animportant baseline to evaluate the continuing role of race and ethnicity inshaping stratification outcomes in American society.

P1: GDZ0521849934c05.xml112CB844-Rutter0 521 84993 4February 4, 20055:25Charles Hirschman and Jennifer C. LeeRace and Ethnic Inequality in Educational AttainmentRace and ethnic differentials in educational enrollment and attainmentnarrowed over the twentieth century, but remain significant ( Jaynes andWilliams, 1989; Lieberson, 1980; Mare, 1995). In addition to an expansionof formal schooling and an increasing emphasis on minimum educationalcredentials for many jobs, a variety of political and social changes haveheightened the demand for increased schooling at all levels. The civil rightsrevolution and the demise of state-supported segregated schooling, if notof de facto segregation, reinforced popular claims for greater access andparticipation in schooling and other domains. Many colleges and universities, with intermittent support from government and foundations, havealso encouraged greater representation of minorities in admissions andscholarships.There remain, however, significant disparities in college attendance bysocioeconomic origins and by race and ethnicity. African American andHispanic youth are much less likely to enter and graduate from collegethan White youth. However, not all race and ethnic minorities are educationally disadvantaged. Asian American students are more likely to attendcollege than any other group, and many new immigrants (and the childrenof immigrants) have above-average levels of educational enrollment andattainment (Hirschman, 2001; Mare, 1995).Based on the 1990 Population Census, Figures 5.1 though 5.4 show thehistory of race and ethnic disparities in educational attainment with a focus on four critical educational continuation ratios. (The source data arepresented in Appendix Table 5.A1.) Educational continuation ratios aresimply the conditional probabilities of advancement from one educationallevel to another (B. Duncan, 1968). The transitions highlighted here are:(1) the proportion of a birth cohort that completes ninth grade, (2) the proportion of those who completed ninth grade who go on to graduate fromhigh school, (3) the proportion of high school graduates who enter college,and (4) the proportion of college entrants who complete college. In thesegraphs, continuation ratios are expressed per 1,000 eligible students.The ten birth cohorts, ranging from 1916–1920 (age 70–74 in 1990) to1961–1965 (age 25–29 in 1990), represent generations of students who werein the school-going age range from approximately the mid-1920s to theearly 1980s. Across these generations, there has been increasing schoolingfor all race and ethnic groups, and educational disparities have generallybeen reduced, especially in graded schooling (from grade 1 through highschool). The trends, however, have been uneven, and there are signs ofwidening race and ethnic disparities in access to and completion of highereducation.Among those who started school before World War II, there was a widegap in the schooling of Whites and all minorities (Figure 5.1). More than

P1: GDZ0521849934c05.xmlCB844-Rutter0 521 84993 4February 4, 20055:25Ethnic Inequality in Educational Attainment113Completion Ratio1000WhiteBlackAmer. 93619401946195019561960Birth Cohortfigure 5.1. Educational Transition Ratio of Persons Completing 9th Grade per1000 Persons by Birth Cohort and Race and Ethnicity.80 percent of White (non-Hispanic) students in the pre–World War II generations reached high school or beyond. In contrast, only about 55–65 percent of racial minorities reached the ninth grade among cohorts who wereattending school in the 1920s and 1930s, and only about 45 percent ofCompletion Ratio1000WhiteBlackAmer. 93619401946195019561960Birth Cohortfigure 5.2. Educational Transition Ratio of Persons Completing 12th Grade per1000 Persons who Completed 9th Grade by Birth Cohort and Race and Ethnicity.

P1: GDZ0521849934c05.xmlCB844-Rutter0 521 84993 4February 4, 20055:25Charles Hirschman and Jennifer C. Lee114Completion Ratio1000WhiteBlackAmer. 93619401946195019561960Birth Cohortfigure 5.3. Educational Transition Ratio of Persons Completing Some College per1000 Persons who Completed High School by Birth Cohort and Race and Ethnicity.Hispanics reached high school. Not all Hispanics and Asian Americanswere native born, so their lower educational attainments reflect, in part,the characteristics of immigrants who were schooled in their countries oforigin. With the exception of the Hispanic population, the racial gap in700Completion Ratio600WhiteBlackAmer. 61930193619401946195019561960Birth Cohortfigure 5.4. Educational Transition Ratio of Persons Completing Bachelor’s Degreeper 1000 Persons who Completed Some College by Birth Cohort and Race andEthnicity.

P1: GDZ0521849934c05.xmlCB844-Rutter0 521 84993 4Ethnic Inequality in Educational AttainmentFebruary 4, 20055:25115the proportions reaching high school gradually narrowed over the middledecades of the twentieth century. By the mid-1950s, more than 90 percentof minority groups reached ninth grade or higher, though the figure wasonly 80 percent for Hispanics as late as the mid-1980s.The educational transition from ninth grade to high school graduation(Figure 5.2) shows two broad patterns. On one hand, Whites and Asiansincreased their rate of high school graduation (of those who entered highschool) from about 75–80 percent in the 1920s and 1930s to more than90 percent by the 1960s. These rates have remained at this high plateau forthe last three or four cohorts in the time series. Starting at a much lowerlevel (around 50–60 percent), the high school graduation rates of AmericanIndians, Hispanics, and African Americans rose for several decades before reaching a plateau of 70–80 percent for the past few decades. AfricanAmericans have made the most progress, rising from approximately50 percent to 80 percent over these decades. The high school graduationrates for American Indians and Hispanics are only a few points belowthose of African Americans, but there are troubling signs of decline in thetransition to high school graduation during the late 1970s and early 1980s.Perhaps the most important educational transition is from high school tocollege. Historically, this figure was about 50 percent, and it may even havedeclined a bit as the number of students reaching high school increasedin the early and mid twentieth century (B. Duncan 1968, p. 623). Thesedata, based on the 1990 Census, show modest gains in the proportions ofhigh school graduates who went on to college from the 1940s to the 1960s(Figure 5.3). The most dramatic rise in this time series is the increasing proportion of Asian American high school graduates who go on to college.Among recent cohorts, about 80 percent of Asian American high schoolgraduates make the transition to college, while the comparable figure is inthe mid 60 percent range for Whites and in the 50 percent range for otherrace and ethnic groups. There has been a slight decline of a few percentagepoints in the transition from high school to college in the decades afterthe 1960s (more than 10 percentage points for American Indians). Mare(1995, p. 166) observes that these declines were primarily among men, forwhom college attendance was inflated during the 1960s as a means to avoidmilitary conscription during the Vietnam War era.The final chart, Figure 5.4, shows the transition from entry into college(any postsecondary schooling) to the completion of a bachelors degree.There have been more fluctuations than linear change in this indicator.A little more than 40 percent of Whites who began college completed abachelors degree in the 1930s; this figure rose to about 50 percent in thelate 1960s and then declined to the mid-40s in the 1970s and 1980s. Thetransition ratio for Asian American students has been 10 to 20 percentage points higher than for White students, while the comparable figuresfor other minority groups are about 10 percentage points below Whites.

P1: GDZ0521849934c05.xml116CB844-Rutter0 521 84993 4February 4, 20055:25Charles Hirschman and Jennifer C. LeeThe majority–minority gap for this ratio widened in recent decades, withfalling rates of college completion for Black, Hispanic, and AmericanIndian students. For the youngest cohort, those born in the early 1960s,fewer than one in five of American Indian students who begin collegereceives a bachelors degree.The Survey of High School Seniors in the Pacific NorthwestTo address the potential sources of race and ethnic educational inequality,and the transition from high school to college in particular, we turn to ananalysis of plans (abstract and concrete) for college based on two surveysof high school seniors in a metropolitan public school system in the PacificNorthwest in the spring of 2000 and 2002. With the cooperation of the local school administration, we administered an in-school paper and pencilquestionnaire to senior students in the five comprehensive high schoolsin the district. In some schools, seniors completed the survey in regularclassrooms, while in others, the students were assembled in an auditoriumto take the survey. Overall, student cooperation was very good; fewer than2 percent of seniors or their parents refused to participate. For seniors whowere absent from the school, we conducted four follow-up mailings, usingthe procedures recommended by Dillman (2000). The follow-up mailingsincreased our sample by more than 20 percent, for a total of 2,357 respondents (1,156 in 2000 and 1,201 in 2002).Evaluation of the completeness of coverage of the senior class surveyis clouded by the uncertainty in defining the universe of high school seniors, and the logistics of locating students who are nominally registeredas high school students, but are not attending school on a regular basis. Intheory, high school seniors are students who have completed the eleventhgrade, are currently enrolled in twelfth grade, and are likely to graduatefrom high school at the end of the year. In practice, however, there are considerable variations from this standard definition. Some students considerthemselves to be seniors (and are taking senior classes and are listed as seniors in the school yearbook), but are classified in school records as juniorsbecause they have not earned sufficient credits. In addition to fourth-yearjuniors, there are a number of fifth-year seniors, who were supposed tohave graduated the year before. Many of the fifth-year seniors are enrolledfor part of the year or are taking only one or two courses in order to obtainthe necessary credits to graduate. Because of their infrequent attendancein high school and low level of attachment, both fourth year juniors andfifth year seniors are underrepresented in our survey.About 10 percent of seniors in the school district are not enrolled in regular high schools, but are assigned to a variety of alternative programs forstudents with academic, behavioral, or disciplinary problems or are beinghome-schooled. Many of these seniors have only a nominal affiliation with

P1: GDZ0521849934c05.xmlCB844-Rutter0 521 84993 4Ethnic Inequality in Educational AttainmentFebruary 4, 20055:25117the public schools – the largest number of such students were enrolled inhigh school equivalency courses at community colleges – and were notmotivated to respond to our request to complete a survey of high schoolseniors. Even among students enrolled in the comprehensive high schools,there were a considerable number of nonmainstream students who completed the survey at lower rates than others. This includes the 6 percentof seniors who were taking community college classes for college creditand another 7 percent of students who were in special education classesfor part or all of the school day.All of these problems affected the response rate to our survey andmake it difficult to offer a precise measure of survey coverage. For regularstudents – graduating seniors at one of the five major high schools – theresponse rate is around 80 percent. If we consider a broader universe ofstudents, including students with marginal affiliation to high school andother hard-to-contact students, our effective rate of coverage of all potential seniors is probably considerably less – perhaps around 70 percent.Although our rate of survey coverage of all high school seniors is less thandesirable, the problems we encountered are endemic in student survey research. Most studies of high school students that are limited to studentswho are present on the day the survey is conducted will have even lowerresponse rates.Our primary independent variable in this study is race and ethnicity.Following the new approach to measuring race from the 2000 census, thesenior survey allowed respondents to check one or more race categories(Perlmann & Waters, 2002). The responses to the race question were combined with a separate survey question on Hispanic identity to create aset of eight mutually exclusive and exhaustive race and ethnic categoriesthat reflect the considerable diversity in the population of youth in WestCoast cities (see the stub of Table 5.1). Although most students have an unambiguous race and ethnic identity, there is a significant minority of students of mixed ancestry and some who refuse to give a response. In futureresearch, we plan to investigate the complexity and nuances of race andethnic measurement, but here our goal is to assign a single best race/ethniccategory to each student. This requires developing a set of procedures forassignment of persons reporting multiple identities and for those who didnot respond.We established a hierarchy of groups to give precedence for assignmentto one category if multiple groups were listed. This hierarchy follows theorder of groups listed in Table 5.1. For example, if a student respondedpositively to the question on Hispanic identity, they were assigned to theHispanic group (first category in Table 5.1) regardless of their responseto the race question. About half of Hispanic students checked the othercategory on the race item and wrote in a Hispanic, Latino, or a specific LatinAmerican national origin. Most of the rest of Hispanics checked White on

P1: GDZ0521849934c05.xmlCB844-Rutter0 521 84993 4February 4, 20055:25Charles Hirschman and Jennifer C. Lee118table 5.1. College Plans and Applications Among High School Seniors in 2000and 2002 in a Metropolitan School District in the Pacific Northwest, by Race andEthnicityCollege Plans for FallFour YearTwo YearNo/DKApplied toCollegeSampleSize(1)(2)(3)(4)(5)HispanicAfrican AmericanEast AsianCambodianVietnameseFilipino & OtherAsianAm Ind/Hawaii/Pac 2,357Race/Ethnicitythe race item, but there were smaller numbers who identified as Black orsome other group. The next category is African American, which includesall non-Hispanic students who checked Black. About one third of studentswho checked Black also checked one or more additional races (Black/Whiteand Black/American Indian were the most common). Assuming that moststudents who report partial Black ancestry have experiences similar tothose reporting only Black, we have opted for the more inclusive definition,excluding only Hispanics.The same logic is applied to the o

United Statesupwards of 85 to 90 percent of American adolescents gradu-ate from high school (or receive a GED certification) is also a product of the availability of free public high schools and laws requiring attendance in 107. Charles Hirschmanand Jennifer Lee. 2005. Race and Ethnic Inequality in Educational Attainment in the United States.

Race and Class Inequality Exam Reading List (10/2017) Race vs. Class, Gender, etc. Sociologists debate the role of race in people’s lives. Some argue that race has a significant role in people’s lives while others argue that race is unimportant or less important than other factors.

Income inequality has two components: (a) ‘market’ inequality and (b) govern-ment redistribution via taxes and transfers. In principle, the two can be combined in any of a variety of ways: low market inequality with high redistribution, low market inequality with low redistribution, high market inequality

Measuring economic inequality Summary Economics 448: Lecture 12 Measures of Inequality October 11, 2012 Lecture 12. Outline Introduction What is economic inequality? Measuring economic inequality . Inequality is the fundamental disparity that permits one individual certain

Robert Shapiro B ENEVOLENT M AGIC & L IVING P RAYER R OBERT S HAPIRO LIGHT TECHNOLOGY . Explorer Race series The Explorer Race ETs and the Explorer Race Explorer Race: Origins and the Next 50 Years Explorer Race: Creators and Friends Explorer Race: Particle Personalities The Explorer Race and Beyond Explorer Race: The Council of Creators

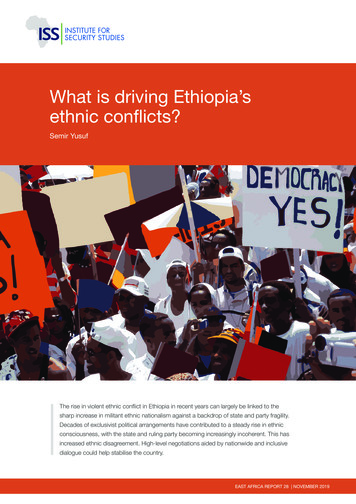

ethnic mobilisation. Finally, debates continued between ethnic and Ethiopian nationalists on such fundamental issues as the history, identity and future destiny of the country. Above the cacophony of ethnic and anti-regime agitations prevailed a semblance of order and overall stability.15 Violent inter-ethnic conflicts erupted occasionally over 27

ethnic fruits, vegetables, and . herbs, particularly in larger cities. One obvious reason for this is the increased ethnic diversity of these areas. Many ethnic groups, including Hispanics, have a high per capita consumption of fresh produce. Also contributing to the increased demand for ethnic produce is a greater emphasis

how our results depend on the political power distribution across ethnic groups. We show that the relationship between inequality and conflict is driven by changes in the distribution of rainfall between the politically most powerful ethnic group and the other groups. To zoom in even further, we complement the analysis at the country level with an

Automotive EMC testing with Keysight Jon Kinney RF/uW Applications Engineer 11/7/2018. Page How to evaluate EMI emissions with a spectrum/signal analyzer ? Keysight EMI Solutions 2 . Page Getting started –Basic terms Keysight EMI Solutions EMI, EMS, EMC 3 EMI EMS EMC Today, We focus here ! Page Why bother? EMC evaluation is along with your product NPI cycle 4 EMI Troubleshooting EMI Pre .