Disturbance To Brown Pelicans At Communal Roosts In .

Disturbance to Brown Pelicansat Communal Roosts inSouthern and Central CaliforniaPrepared for theAmerican Trader Trustee CouncilCalifornia Department of Fish and GameUnited States Fish and Wildlife ServiceNational Oceanic and Atmospheric AdministrationByDeborah Jaques and Craig StrongCrescent Coastal Research112 West Exchange St.Astoria, Oregon97103October 15, 2002

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYDisturbance to Brown Pelicans at communal roosts in southern and central California wasassessed using data from 235 flushing events observed over the period 1986-2000. This studywas conducted to provide quantitative information on frequency, severity and sources ofdisturbance, to aid the American Trader Trustee Council (ATTC) in selecting and prioritizingrestoration projects intended to enhance roost quality for the California Brown Pelican.Disturbance frequency in southern California averaged 0.53 flushing events per hour. Frequencyand severity of disturbances to roosting pelicans in southern California were greatest in naturalhabitats, such as river mouths and other estuaries, and lowest at harbors and man-made structuresalong the outer coast. Eighty-five percent of all pelicans observed to flush due to disturbancewere roosting in natural landscapes. Disturbance occurred about once an hour at estuarine roostsversus once every four hours on artificial substrates. More than 90% of all disturbance incidentswere directly due to humans, mostly recreationists, rather than natural factors. Pelicansdemonstrated habituation to the most common types of boat traffic in harbors. Humandisturbance at southern California natural areas may be incurring relatively high energetic coststo immature pelicans and precluding regular use of otherwise desirable habitats by adults.Efforts to reduce disturbance will target different user groups, primarily recreationists, and varyaccording to roost habitat type. Artificial structures along the southern California coast are acritical component of nonbreeding habitat for Brown Pelicans, however the results of this studysuggest that restoration actions geared towards reducing human disturbance at existing roostsshould prioritize natural areas. Public education, establishment of 25-30 meter buffer zonesbetween traditional pelican sites and people, and habitat manipulation to enhance or create islandroost habitat are recommended.Disturbance indices for two key central California roost sites included in this study were higherthan for any southern California sites. Human disturbance frequency increased greatly in 19992000 compared to levels documented in the 1980's. Kayaks and ecotourism, along with habitatand water level management changes at the Moss Landing WA were responsible for much of thedisturbance documented. Kayaks and other boats caused 77% of all observed disturbance eventsat these roost sites in 1999-2000. Immediate management intervention is recommended.ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis analysis was supported by the American Trader Trustee Council (ATTC) and the NationalFish & Wildlife Foundation. Special thanks to Carol Gorbics (USFWS), Paul Kelly (CDFG)and Jennifer Boyce (NOAA) for facilitating the project. The ATTC supported field work in1999-2000. Historical data were provided thanks to research funded, supported, or incooperation with, Dan Anderson (UC, Davis), Dave Harlow (USFWS), John Gustafson andPaul Kelly (CDFG, Sacramento), Harry Carter (Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA), TomKeeney (Naval Base Ventura County, Point Mugu California), and Janet Didion (CaliforniaDept. of Recreation, Sacramento). Laird Henkel (H.T. Harvey and Associates), Bradford Keittand Holly Gellerman (Island Conservation and Ecology Group) assisted with field surveys in2000. This report was improved by reviews from Carol Gorbics and Paul Kelly.i

TABLE OF CONTENTSEXECUTIVE SUMMARY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iACKNOWLEDGMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iCONTENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .iiINTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1METHODS. 1RESULTS. 3Southern California . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Disturbance Frequency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Disturbed Habitats . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Disturbance Types and Pelican Response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Flushing Distances . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Disturbed Locations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Central California . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Pismo-Shell Beach Area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Moss Landing Area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16DISCUSSION. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17RECOMMENDATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20Southern California . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Harbors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Estuaries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Central California . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .LITERATURE CITED20202324. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24ii

LIST OF FIGURESFigure 1.Figure 2.Figure 3.Figure 4.Figure 5.Figure 6.Frequency of human disturbance by habitat type in southern California . . . . . . . . 5Sources of disturbance to roosting pelicans in southern California . . . . . . . . . . . . 7Sources of disturbance by habitat type in southern California . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8Mean pelican flushing distances in southern California . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10Sources of disturbance to pelicans in the Pismo-Shell Beach area . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14Sources of disturbance to pelicans in the Moss Landing area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15LIST OF TABLESTable 1.Table 2.Table 3.Table 4.Table 5.Table 6.Disturbance frequency at selected southern California roost sites . . . . . . . . . . . . .Brown Pelican response to disturbance by source type . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Disturbance frequency at Pismo-Shell Beach pelican roosts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Disturbance frequency at Moss Landing area pelican roosts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Summary recommendations to reduce human disturbance in natural habitats . . . .Summary recommendations to reduce human disturbance in harbors . . . . . . . . . .iii4913132122

INTRODUCTIONHuman disturbance causes direct and indirect effects on birds in nonbreeding habitats that areoften difficult to measure. The most obvious direct effect is flight behavior, which in itselfcauses variable levels of energy expenditure, depending on the metabolic cost of flight byspecies, duration and type of flight (Pennycuik 1972). Chronic disturbance to nonbreeding birdscan affect body condition, metabolic rate, habitat use, and subsequent reproductive success dueto reduced lipid reserves (Stahlmaster 1983, Josselyn et al. 1989, Culik 1990, Gaston 1991).Long-term effects on bird distribution and habitat use have been inferred (Batten 1977, Burger1981, Jaques and Anderson 1986, Cornelius et al. 2001).Based on the anatomy, roost site selection and behavior of the California Brown Pelican(Pelecanus occidentalis californicus), it is evident that conserving energy is an important lifehistory trait for these large migratory birds. Brown Pelicans spend much of their daily energybudget resting and maintaining plumage at traditional communal roosts (USFWS 1983, Croll etal. 1986). The less disturbance that pelicans experience at these roosts, the less energy they willexpend responding to such events and the more energy they will be able to conserve by usingfavored locations of the coast and selected microhabitats within roosts. The quality of a roostsite can be based then, in part, on measurements of disturbance frequency and severity.Habitat availability, habitat selection, and disturbance to roosting Brown Pelicans are allinterrelated. Brown Pelicans prefer to roost communally on dry substrate surrounded by wateron all sides to avoid predators, particularly at night. During the day, locations that have less of awater buffer are often selected, since these areas may be in nearest proximity to food or haveother attractive features (USFWS 1983, Strong and Jaques 2002). Roost sites that are not trueislands are most vulnerable to disturbance. Nearshore island habitat is limited in southernCalifornia and human disturbance at roosts has been a management concern (USFWS, 1983,Jaques and Anderson 1988, Jaques et al. 1996, ATTC 2001, Capitolo et al. 2002).This study was conducted to provide additional quantitative information on disturbance toBrown Pelicans in southern California, including analysis of frequency, severity and cause ofdisturbances. The results are intended to aid the American Trader Trustee Council (ATTC) inmaking plans for restoration projects intended to reduce disturbance and enhance roost quality.METHODSObservations and censuses of Brown Pelicans at communal roosts were made as part of ATTCrestoration activities during 1999-2000 and as part of various projects for other purposes during1986-1993. Disturbance data from 1986-1987 were collected as part of a master’s thesis project(Jaques and Anderson 1987, Jaques 1994). Focused studies of disturbance and roost habitat usewere made at and around Mugu Lagoon from 1991-1993 (Jaques et al. 1996) and at MossLanding in 1987 (Jaques and Anderson 1988). Those data have been incorporated into thisanalysis where noted. Other data included in this report were collected incidental to a study of1

survival of rehabilitated oiled birds (Anderson et al. 1996) and as part of an inventory of marinebird and mammal use of California State Parks (Jaques and Strong 1996). Methods andobservers were fairly consistent throughout this period, allowing comparison of disturbancefrequency and source, by habitat, for all of the data set. Information on Brown Pelican responseto disturbance was available for a subset of the historical data and all of the data collected in2000. Data were grouped as historical (all data collected from 1986-1993) and recent (19992000), for analyses of changes over time.The time and duration of observation, weather conditions and sea state, were recorded at eachroost site. Pelicans were censussed by location and habitat type, with a breakdown of birds byage category. Pelican roost habitat types were categorized as follows:OSR: Offshore rock or island, open coast.CRS: Cliff or Rocky shore, on mainland shore of open coast.BCH: Mainland shore open coast beach, sand or with rocky structure.EST: Estuary. Large estuaries always open to the seaRMO, CMO: River or Creek mouths, that often form smaller estuaries.LAG: Estuaries that are frequently closed off from the ocean by a beach berm.HRB: Harbor. All roost structures associated with harbors.BRW: Detached breakwater. A subhabitat in harbors.JTY: Jetty, attached to mainland. Most often a subhabitat within a harbor, but used asprimary habitat type when not in association with a harbor.MMS: Other man-made structures. Most often a subhabitat in harbor, but a primaryhabitat if on the outer coast.For disturbance analysis, roost subhabitats within harbors were grouped together and referred tounder the “Harbor” except where noted otherwise. River mouths, lagoons, and other estuarieswere also grouped together under the general category “Estuary” in many of the analysis.Disturbance observations were not made at offshore rocks or beaches in southern California.Disturbance to pelicans was defined as an event causing birds to flush rapidly from a roost. Thefollowing parameters were recorded when possible: the cause of disturbance, estimated distancefrom the disturbance source when birds flushed, number of birds flushed, fate of flushed birds(depart roost, relocate to different area, or reland), and any associated information (response ofother species, percent of total roost affected, etc.). Disturbance frequency was measured as thenumber of disturbances per hour of observation. A measure of disturbance severity wasmeasured with a modification of the Disturbance Index, “D,” developed by Jaques et al. (1996)as:(D SQR ROOT N*(n depart*3) (n relocate*2) n relandHours of observation)where N the number of disturbances, and n depart, relocate or reland the number of pelicansshowing that response. Multiplication factors are included to weight more severe disturbanceeffects (departure and relocation).2

Sources of disturbance in southern California were grouped into 12 categories. Ground-baseddisturbances by people were grouped in the category “walker” unless the persons were clearlyengaged in other more specific categories, such as working (“worker”), surfing (surfer), orfishing from shore (“fisher”). Disturbances from watercraft were divided into kayaks, jet skis,and all other boats (fishing boats are grouped with other boats). Aircraft were divided intohelicopters and all other aircraft. Disturbances by dogs, including people walking dogs, wereincluded in the category “dog.” Gun-based hunting and target shooting were grouped togetheras “shoot.” Natural disturbance categories included waves, other wildlife species, and unknowns(no human disturbance recognized, no obvious cause).RESULTSSouthern CaliforniaDisturbance FrequencyWe documented 100 incidents of disturbance to Brown Pelicans in 189 hours of observations atroosts along the southern California mainland. Forty-six of these disturbance events weredocumented in 1999-2000, and 54 were part of the historic data set (Table 1). An additional 133disturbance events were recorded during focused observations at Mugu Lagoon during 1991-93(Jaques et al. 1996); these data were not included in the pooled information for southernCalifornia in this report, except where noted.Disturbance frequency in southern California was 0.53 flushing events per hour over the entiresample period. The overall disturbance rate was slightly higher in southern California in 19992000 than in 1986-93 (Table 1). Disturbance rates were higher at seven roosts, lower at tworoosts, and unchanged at two roosts in the recent period. Observation hours were relatively lowat many southern California sites, however.Disturbed HabitatsFrequency and severity of disturbances to roosting Brown Pelicans in southern California weregreatest in natural habitats, such as river mouths and other estuaries, and lowest at harbors andman-made structures along the outer coast (Fig. 1). Pelicans at natural roosts were disturbed bypeople about once every hour, while pelicans at artificial roost sites were disturbed about onceevery four hours (N 189 hours). Within harbors, pelicans at detached breakwaters weredisturbed less frequently than those at jetties (0.28 compared to 0.36 disturbances/hour). Thetotal number of pelicans observed flushed from all sources was 4,779 birds. Of these, 85% wereroosting on natural substrates, and 16% were on artificial structures. There was a tendency for ahigher proportion of the birds present to flush from a disturbance in a natural setting, comparedto a harbor. All natural roost sites where disturbance was documented had a higher disturbanceindex than the artificially created roost sites (Table 1).3

Table 1. Disturbance frequency and hours of observation at selected Brown Pelican roosts insouthern California, 1986-1993 and 1999-2000. Roost sites are listed roughly in order of mostto least disturbed. Human and natural disturbances are expressed as the number of disturbanceper hour of observation (N). “D” is the Disturbance Index and pertains to data collected in1999-2000 only. The disturbance index is described in Methods.RoostNo.Roost SiteLA 16.0Malibu LagoonSD 1.0Hab.1986-1993HumanNaturalLAG0.880.15Tijuana SloughEST1.43VN 7.0Santa Clara RiverRMOSD 4.0Point Loma CliffsSD (.1)-La Jolla CliffsCRSNDND01.002.05.8LA 11.0King HarborHRB00(3.0)0.750(8.0)4.9OR 3.0Dana Point HarborHRB0.280(14.2)0.580(6.9)1.6VN 5.0Channel IslandsHarborHRB0.402.50.510(3.9)0.5SD 3.5Zuniga PointJTY1.701.800(3.2)0VN 4.0Mugu LagoonEST0.310.10(322)NDND0-VN 8.0Ventura HarborHRB00(2.7)0.350(8.7)1.3SD 12.0Agua HediondaLagoonLAG003.20.280(7.1)4.2LA 12.0Marina del ReyHarborHRB0.290(17.5)0.260(3.8)0.6SD 11.0Batiquitos LagoonLAG001.300(1.4)0OR 10.1Bolsa Chica Lag.LAG001.200(0.1)-SD 13.0Oceanside HarborHRBNDND000(1.2)0SB 4.0Santa BarbaraHarborHRB0012.700(2.3)0SB 3.0Santa BarbaraOuter HarborHRB002.6historic roost siteVN 10.0Mobil Oil PierMMS008.9historic roost site0.430.03(120)*SOCAL TOTAL* does not include Mugu Lagoon4N0.620.04ND(69)29.7

Figure 1. Frequency of human disturbance to Brown Pelicans at roosts in six general habitattypes in Southern California. ‘Disturbance frequency’ is the number of disturbance eventsdocumented per hour of observation in each habitat type. The number of hours spent observingpelicans in each habitat is shown as the sample size on top of each bar. Habitat types aredefined as follows: Harbor all roosting substrates associated with harbors, including jetties,breakwaters and other man-made structures; Jetty jetties on the outer coast, not closelyassociated with harbors; MMS man-made structures not associated with harbors; Shore mainland cliff or rocky shoreline; Lagoon lagoon; River river mouth.5

Disturbance Types and Pelican ResponseThe greatest single source of disturbance was a person(s) on foot, approaching pelicans at aroost. This accounted for 32% of all disturbances seen from 1986-2000. In most cases thepeople were simply walking, but a few incidents involved more specific types of activities e.g.,jogging, photographing. The second largest source of disturbance was from water-basedrecreational sports, including boating, surfing and fishing. Disturbances from watercraft andsurfers were proportionally greater in 1999-2000 than in 1986-93 (Fig. 2). Collectively, thesesports accounted for 13% of all disturbances in the early period compared to 37% in the latterperiod. In contrast, documented disturbances involving dogs decreased, from 17% of alldisturbances in 1986-93, to 2% in 1999-2000. Natural disturbances were rare in southernCalifornia and accounted for less than 10% of all disturbances (N 100 disturbances).Characteristic types of disturbance differed by habitat. In harbors, 50% of all disturbance eventswere caused by watercraft of some type, and 20% of disturbances were caused by fishermen onfoot (Fig. 3). In estuarine habitats, 62% of all human disturbances were caused by peopleapproaching pelicans on foot (including surfers); an additional 20% of events observed werecaused by people with dogs.The disturbance

along the outer coast. Eighty-five percent of all pelicans observed to flush due to disturbance were roosting in natural landscapes. Disturbance occurred about once an hour at estuarine roosts versus once every four hours on artificial substrates. More than 90% of all disturbance incidents

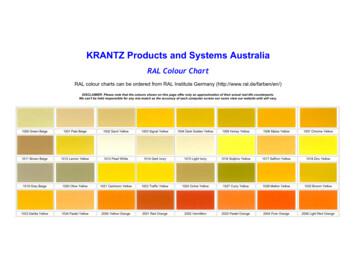

8002 Signal Brown 8003 Clay Brown 8004 Copper Brown 8007 Fawn Brown 8008 Olive Brown 8011 Nut Brown 8012 Red Brown 8014 Sepia Brown 8015 Chestnut Brown 8016 Mahogany Brown 8017 Chocolate Brown 8019 Grey Brown 8022 Black Brown 8023 Orange Brown 8024 Beige Brown 8025 Pale Brown. 8028 Earth Brown 9001 Cream 9002 Grey White 9003 Signal White

Flamingos and Pelicans and some small migratory birds. It was highly satisfying to note that some of the migratory birds like pelicans could be observed in sizeable numbers in the sanctuary area during the off seas

the New Orleans Saints and New Orleans Pelicans as Owner, succeed-ing her husband, Tom Benson, who passed away on March 15, 2018, after serving as the Owner of the Saints since 1985 and the Pelicans franchise since 2012. The New Orleans native is an ac

4. Active Disturbance Rejection Control . The active disturbance rejection control was proposed by Han [9][10][11][12]. It is designed to deal with systems having a large amount of uncertainty in both the internal dynamics and external disturbances. The particularity of the ADRC design is that the total disturbance is defined as

ON ACTIVE DISTURBANCE REJECTION CONTROL: STABILITY ANALYSIS AND APPLICATIONS IN DISTURBANCE DECOUPLING CONTROL QING ZHENG ABSTRACT One main contribution of this dissertation is to analyze the stability char-acteristics of extended state observer (ESO) and active disturbance rejection control (ADRC).

practical control strategy that is Active Disturbance Rejection Control (ADRC) [10-14] to the EPAS system. The controller treats the discrepancy between the real EPAS system and its mathematical model as the generalized disturbance and actively estimates and rejects in real time, the disturbance

e recently developed active disturbance rejection con-trol (ADRC) is an e cient nonlinear digital control strategy which regards the unmodeled part and external disturbance as overall disturbance of the controlled system [ ] . e ADRC mainly consists of a tracking di erentiator (TD), an extended state observer (ESO), and a nonlinear state error

fructose, de la gélatine alimentaire, des arômes plus un conservateur du fruit – sorbate de potassium –, un colorant – E120 –, et deux édulco-rants – aspartame et acésulfame K. Ces quatre derniers éléments relèvent de la famille des additifs. Ils fleuris-sent sur la liste des ingrédients des spécialités laitières allégées .