Third Generation Of Modern Architecture And Contemporary .

Seasoned Modernism. Prudent Perspectives on an Unwary Past 55Third Generation of Modern Architecture andContemporary Spanish Architecture.Jørn Utzon’s LegacyJaime J. Ferrer ForésPhD, Associate Professor, Barcelona School of Architecture (ETSAB), Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spainjaime.jose.ferrer@upc.eduKEYWORDS: modern organicism; regional work; formal analogies; poetic workIntroductionJørn Utzon has had a significant influence upon contemporary architecture across the world,and his legacy has inspired many outstanding contemporary architects, particularly in Australia,Denmark and Spain. While Alvar Aalto is considered to be at the forefront of the SecondGeneration of modern architects, who responded to the orthodoxy of the Modern Movementand the earlier interpretation of functionalism in a humanistic-oriented architecture,1 Utzon isthe central figure of the “Third Generation of modern architecture in the 20th century,” whoreacted against the dogmas of modern architecture altogether, leading it into “a new phase ofcriticism, renewal and maturity.”2 As Christian Norberg-Schulz writes, “the First Generation ofmodern architects liberated space, the Second returned things to us, and the Third, with Utzonas the protagonist, has united it all as a down-to earth expression. In this way he has opened upthe way for the future generations of the new tradition.”3Sigfried Giedion also considered that the Danish architect Jørn Utzon typifies the ThirdGeneration.4 The fifth edition of Space, Time and Architecture (1967) includes a list of attitudesin order to differentiate the Third Generation from the early phases of Modern Movement: thesocial orientation; open-ended planning with the incorporation of changing conditions; greatercarefulness in handling the existing situation and an emphasis upon the architectural use ofhorizontal planes and platforms; a stronger relation to the past expressed in the sense of a desirefor continuity and finally the right of expression above pure function.5 To Sigfried Giedion, this“new chapter in contemporary architecture”6 was opened by the work of Jørn Utzon.International journals such as Zodiac turned the architecture of Jørn Utzon into a fixedreference in the Spanish architecture. As Christian Norberg-Schulz pointed out, with hisregional and universal work, “Utzon gave Modern Architecture a new dimension. Todayhis lesson unfortunately seems to have been forgotten by most people.”7 However, in Spain,1 Antón Capitel, “The Third Generation, or some of the Swan Songs of the Modern Movement,” ZARCH 10(2018): 29.2 Philip Drew, Third Generation. The changing Meaning in Architecture (London: Pall Mall Press, 1972):3,7. Philip Drew is also the author of the The Masterpiece: Jørn Utzon. A secret life (South Yarra, Victoria:Hardie Grant Books, 1999) and Sydney Opera House. Jørn Utzon (London: Phaidon, 1995).3 Christian Norberg-Schulz, “Jørn Utzon and the ‘New Tradition’,” in Utzon and the new tradition(Copenhagen: The Danish Architectural Press, 2005), 258.4 Sigfried Giedion, “Jørn Utzon and the Third Generation,” Zodiac 14 (1965): 36-47.5 Sigfried Giedion, Space, Time and Architecture, the Growth of a New Tradition (Cambridge: HarvardUniversity Press, 1967).6 Ibid., 689.7 Norberg-Schulz, “Jørn Utzon and the ‘New Tradition’,” 258.

56 studies in History & Theory of ArchitectureUtzon’s work seems closer and more relevant than ever,8 as it has inspired many outstandingcontemporary architects, such as Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza, Antonio Fernández Alba,Rafael Moneo, Alberto Campo Baeza, Carlos Ferrater, Nieto & Sobejano, Mansilla Tuñón,and RCR Arquitectes. Utzon is a continuous inspiration for the architects and students ofarchitecture, which can be traced in the way they work and express themselves, thus provingwhat William J. R. Curtis wrote, that “his magical inventions are liable to inspire peoplefor a long time to come.”9 Nordic architecture became a constant reference in the Spanisharchitecture of the 1950s, at first through international journals, and later through architects’travels.10 The most outstanding architects of the Madrid School11 and the Barcelona School128 Jaime J. Ferrer Forés and Noelia Cervero Sánchez, “Centenaries of the Third Generation,” ZARCH 10(2018): 2-5.9 William J. R. Curtis, “The substance of architectural ideas: Jørn Utzon,” Arkitektur 1 (2009): 6.10 Jaime J. Ferrer Forés, “La arquitectura nórdica a través de las revistas españolas” [“Nordic ArchitectureThrough Spanish Journals”], in Las revistas de arquitectura (1900-1975): crónicas, manifiestos,propaganda, ed. José Manuel Pozo et al. (Pamplona: T6 Universidad de Navarra, 2012): 475-482.11 Juan Daniel Fullaondo, “La Escuela de Madrid” [The Madrid School], Arquitectura 118 (1968):11-23.12 Oriol Bohigas, “Una posible Escuela de Barcelona” [A Possible School of Barcelona], Arquitectura 118(1968): 24-30.Fig. 1: Jørn Utzon. Market in Elineberg, 1960 Rafael Moneo. Competition entry for the market in Cáceres,1962

Seasoned Modernism. Prudent Perspectives on an Unwary Past 57developed a modern organicism associated with the ideas of Bruno Zevi and the inspirationfrom the work of Frank Lloyd Wright and Nordic neo-empiricism.13 Several projects beganto adopt an abstract language moderated by climate and urban environment with theMediterranean modernity of works by Coderch or Antonio Bonet Castellana. This realistmodernity materialized some remarkable works during the sixties with the incipient politicalopenness and the stylistic mutations from rationalism to a mature modernity.During the sixties and seventies, economic prosperity and touristic development gave way tothe progressive modernization of Spain, with the boom of industrialization and urbanization.Two architectural trends coexisted: an idealistic approach, a trend derived from rationalism andmodern technology, and a realistic attitude close to the nature of materials that later evolved intoBrutalism with the strong constructive expressiveness using reinforced concrete.Considering this context, the paper attempts to approach Utzon’s influence on Spanisharchitecture by analyzing the various influences, from formal analogies to the more subtlereinterpretations of his legacy. The key figure is Rafael Moneo, who worked in Utzon’s office inDenmark, thus gaining thorough knowledge of his work, way beyond the catalog of projects.Moneo tried to apprehend his lessons and reinterpret them, which is why the reference toUtzon is never literal in his own work. Other architects, however, introduced and explicitlyused formal features of Jørn Utzon’s architecture, proving their interest in his works but oftenrepeating formal gestures.Place and Culture: Rafael MoneoRafael Moneo (1937) obtained his architectural degree in 1961, and worked as a student,from 1958 to 1961 with Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza and later on, from 1961 to 1962in Hellebæck with Jørn Utzon.14 Here, he had a close view of Utzon’s approach, carefullyassimilating and fusing already existing techniques or formal inventions into his personalsynthesis. Utzon filtered the natural forms, structures and details derived from vernacularbuildings and constructive tradition as sources of inspiration,15 as stated in the quote of the juryfor the 2003 Pritzker Architecture Prize, given to Jørn Utzon: “He rightly joins the handful ofmodernists who have shaped the past century with buildings of timeless and enduring quality.”16Utzon’s work emphasizes his appreciation for nature and his capacity to read the context with arespectful insertion in the environment as a result of the awareness of the territory.Moneo’s first project developed after he worked at Jørn Utzon’s office in Hellebæk was acompetition proposal for a Market in Cáceres (1962), which won the second prize. Moneo’scompetition proposal, with the slender elegance of his impluvium floating roof and thesculptural opulence of his straight-line platforms rooted in its context, is characterized by theopposition between the bold concrete forms of the platforms and the lyrical gestures of thefloating roofs which recall Utzon’s project for a market in Elineberg (1960). (Fig.1)His early organicism and sensitivity for the urban context was shown in his proposal fora Broadcasting Station at El Obradoiro Square in Santiago de Compostela (1962) witha delicate exercise of repetition and variation combining pieces of different sizes in anorchestrated articulation whose shifting profile effortlessly integrates the building in thefragmented landscape of the Obradorio and recalls Utzon competition project for the13 Gabriel Ruiz Cabrero, El Moderno en España: Arquitectura 1948-2000 (Sevilla: Tanais Ediciones): 43-52.14 Rafael Moneo (Tudela, 1937), architect and Professor at Barcelona School of Architecture, Madrid andHarvard. Rafael Moneo worked in Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza and Jørn Utzon offices in the earlysixties. Pritzker Prize, 1996.15 Kenneth Frampton, “Jørn Utzon: Transcultural Form and the Tectonic Metaphor,” in Studies in TectonicCulture. The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture, ed. John Cava(Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1996), 247-298.16 https://www.pritzkerprize.com/laureates/2003, last accessed Sept 24, 2019.

58 studies in History & Theory of ArchitectureFig. 2: Jørn Utzon. Aalborg Convention Center, 1945 Rafael Moneo. Project for a building at ObradorioSquare, Santiago de Compostela, 1962Aalborg Convention Centre (1945). Professor Luis Moya, one of the jurors for the prize,wrote: “The architecture that Moneo designed seemed older than the pre-existing architecturein the square.”17 With this project, Moneo obtained a fellowship at the Spanish Academyin Rome (1963-1965), where he designed his organic competition proposal for the MadridOpera House (1964). The sculptural expressiveness of the proposal was clearly inspired byAalto and equally touched by the work of Utzon. (Fig. 2)Filtered by a personal expressivity, his initial organic sensitivity gave way to a personallanguage emphasizing the site’s conditions and tectonic form, exemplified by works such asthe Bankinter offices in Madrid (1972-1977), the Museum of Roman Art in Mérida (19801986) or the Kursaal in San Sebastian (1990-1999).18 To Rafael Moneo, architecture emergesfrom the place and program in an intense design process. Inserted in the fabric of the cityand imbued with the spirit of the site’s conditions, Moneo’s project for the Souks of Beirut(1996-2009) provides an organizing structure arranged longitudinally, in a serial form withthe presence of skylights, which echoes traditional Islamic architecture.19 His urban designapproach provides a dense network of spaces that retain the urban characteristics of the placeconnecting the streets to the Souks. (Fig. 3)17 Rafael Moneo, “Anteproyecto de edificio destinado a centro emisor en la Plaza del Obradoiro. Premio deRoma,” Arquitectura 50 (1963): 19-22.18 Rafael Moneo, Rafael Moneo: 1967-2004 Imperative anthology, El Croquis 20 64 98 (2004).19 Ibid., 480-483.

Seasoned Modernism. Prudent Perspectives on an Unwary Past 59Fig. 3: Jørn Utzon. Farum town centre, 1966 Rafael Moneo. Souks of Beirut, 1996-2009Moneo’s proposal recalls Utzon’s competition project for Farum town centre (1966), whichwas also inspired by Islamic bazaars. Utzon conceived his proposal by the addition of differentunits around a central spinal column whose significant characteristics evoke the tradition of theIslamic bazaars. Utzon’s work combines the construction with both the elements of modernityand the timeless eloquence of anonymous or historic architectures learned in his travels. AsRafael Moneo recalled: “traveling, gaining knowledge about other cities and cultures is acontinuous lesson for architects, who will broaden the horizons of their work and at the sametime verify the universal condition of the discipline.”20 The scheme was designed to grow by theaddition of a set of parts capable of generating the structure of the complexes to be built usinga geometrically flexible system of precast concrete components, growing by means of cellularaddition along a spine giving access to shop units. His Stockholm Museum of Modern Art(1991) is also a project based on repetition and variation and another example of a sensitiveresponse to the site. The hall with a pyramid ceiling and skylight is repeated in groupingscombining different shapes and sizes generating a continuous and varied profile very much inharmony with the landscape of Skeppsholmen Island.21Throughout the slow and patient search for the architectural project, Rafael Moneo elaboratedon Utzon’s approach and combined it with other influences. Moneo’s work flows from theorganicism of his first projects to the composition and abstract aggregation of his latest designs,submitting his personal expression to the characteristics of place and program.20 Rafael Moneo, International Portfolio 1985-2012 (Stuttgart: Axel Menges, 2013), 11.21 Rafael Moneo, Remarks on 21 Works (New York: The Monacelli Press, 2010), 417.

60 studies in History & Theory of ArchitecturePlatforms: Antonio Fernández Alba, Rafael Moneo, and Alberto Campo BaezaUtzon materialized the lyrical essence of his architectural research in feats like the platformcrowned by a canopy of light roofs.22 Most of his proposals of this period are characterizedby large platforms and a determination to define public and symbolic places by means offloating roofs that engage in a dialogue with the landscape.23 As Kenneth Frampton wrote,the earthwork acts as “a necessary landform capable of integrating a structure into the surfaceof the earth.”24 The bold concrete forms of the platforms and the lyrical gestures of the shellsare conceived from a recognizable section, understanding the buildings as part of the territory,with the characteristic modern ambition of blending architecture and nature. The platform isa characteristic feature of Utzon’s architecture, and the contrast between the stereotomic andmassive platform and the free curvature of the roof is also distinctive of his design talent.A few Spanish architects have used the platform to build the site by developing Utzon’s buildingnotion as an artificial landscape. Antonio Fernández Alba (1927) laid the platform out in amanner that might well be directly indebted to Utzon.25 In his proposal for the Madrid OperaHouse competition (1964), he established a rectangular platform, an artificial landform insertedinto the urban fabric, characterized by the opposition between the bold concrete forms of thestaggered platforms and the wide-span floating roofs.26 Fernández Alba’s proposal can be comparedto Utzon’s project for the Madrid Opera House. Covered by S-shaped weightless roofs floatingabove the platform, Utzon’s asymmetrical auditorium is vigorously sculpted out of the massiveplatform and is characterized by a folded-plate roof supported by cables hanging from a tall mast.Fernández Alba’s competition proposal for the Exhibition and Congress Center in Madrid(1965), which obtained the second prize, set out a stepped massive platform where the threeauditoriums appear as if they were carved out of a solid mass in a manner reminiscent to Utzon’splatforms.27 As an organizational strategy, the platform contains the service and secondary spaces,as well as the extensive underground parking and the backstage areas. The broad, rising levels ofthe platform were also arranged to form a public plaza, a gathering place that faces the city. Thesculptural opulence of his straight-line platforms contrasts with the rhythmic elegance of hisfloating roofs. Fernández Alba understood the significance of rising above the ground level of thecity, creating an artificial landscape that makes the building monumental. (Fig. 4)Fernández Alba adapted Utzon’s way of drawing using the shadows cast and light shading tounderline the relief of the platform.28 In those projects, the raised platform is understood as an22 In 1949, Jørn Utzon received the Zacharia Jacobsen Award scholarship to travel to the United States. In thatstudy trip he visited Mies van der Rohe in Chicago and Frank Lloyd Wright in Taliesin. In Chicago, he visitedFarnsworth house work in progress (1945-1950) and in Wisconsin Johnson Wax tower laboratory. Both willexert a remarkable influence in Utzon’s work. The trip continued towards California, where he visited Rayand Charles Eames in their new house at Pacific Palisades, a house built up of industrial prefabricatedelements. The following stage of the trip took him to Mexico. In the Yucatan Peninsula, he visited Uxmal andChichen Itza. Supported by ample horizontal platforms, the constitution of the temples emerged above thedensity of the jungle. The symbolic value of the platforms will exert a great influence on Utzon. The trip toMexico turned into one of his greatest architectural experiences of his life.23 Jørn Utzon, “Platforms and Plateaus: Ideas of a Danish architect,” Zodiac 10 (1962): 112-139.24 Kenneth Frampton, “On Jørn Utzon,” in Utzon Symposium. Nature Vision and Place, ed. Michael Mullinset al. (Aalborg: Aalborg University, 2003), 7.25 Antonio Fernández Alba (Salamanca, 1927), architect and Professor at Madrid School of Architecture.Critical and artistic, he fused the organicist currents of Wright, Aalto and Utzon with Spanish vernaculartradition.26 Antonio Fernández Alba, Antonio Fernández-Alba. Premio Nacional de Arquitectura 2003. Libro defábricas y visiones recogido del imaginario de un arquitecto fin de siglo 1957-2010 [Book of Factoriesand Visions Collected from the Imaginary of an Architect at the End of the 1957-2010 Century] (Madrid:Ministerio de Fomento, 2011), 76-79.27 Ibid., 80-83.28 Carlos Montes Serrano et al., “Architectural Drawing in the Escuela de Madrid during the 1960s,” diségno3 (2018): 149.

Seasoned Modernism. Prudent Perspectives on an Unwary Past 61Fig. 4: Jørn Utzon. Sydney Opera House, 1956-1973 Antonio Fernández Alba. Exhibition and CongressCenter in Madrid, 1965Fig. 5: Rafael Moneo. Competition entry for the Amsterdam Town Hall, 1967-1968

62 studies in History & Theory of Architectureeruption of nature in the city, a fabricated grid-shaped terrain in contrast with natural ground.In Fernández Alba’s competition proposal for the Exhibition Center in Gijón (1966), theraised platform becomes a continuation and evocation of the natural terrain with a lightweightsuperstructure designed with contrasting curvilinear forms seemingly floating above thestaggered platform.29 The raised plateau accentuates the horizontality of the platform and relieson the qualities of the surrounding landscape.Rafael Moneo’s work relies on a deep understanding of the site. The platform creating the baseof his competition proposal for the Amsterdam Town Hall (1967-1968), which was highlycommended, and the wide stairs leading up to it were suggested to Moneo by his work withUtzon and his knowledge of ancient terraced temples, from Mayan monuments to Chinesetemples and Islamic mosques. The platform, anchoring the building to the terrain andcontaining all the spaces needed to serve the Town Hall became a built landscape30 evoking anancient architectural idea with the staggered surfaces and the vast stairway, as a gathering place,a town square, through interconnecting levels, social stairways, and cascading terraces to viewthe spectacle of Amsterdam’s landscape. (Fig. 5)Moneo’s platform remarks the potential of the location and the character of the site. With itsgeometry, which is inspired by the stone blocks of the coastal walls, Moneo referred to theKursaal auditorium in San Sebastian (1990-1999) as a geological event.31 The translucentvolumes of the auditorium and convention center are seemingly stranded along the river,belonging more to the landscape than to the urban surroundings. The platform connects theslanted and luminous volumes of the auditoriums an

criticism, renewal and maturity.”2 As Christian Norberg-Schulz writes, “the First Generation of modern architects liberated space, the Second returned things to us, and the Third, with Utzon as the prot

What is Computer Architecture? “Computer Architecture is the science and art of selecting and interconnecting hardware components to create computers that meet functional, performance and cost goals.” - WWW Computer Architecture Page An analogy to architecture of File Size: 1MBPage Count: 12Explore further(PDF) Lecture Notes on Computer Architecturewww.researchgate.netComputer Architecture - an overview ScienceDirect Topicswww.sciencedirect.comWhat is Computer Architecture? - Definition from Techopediawww.techopedia.com1. An Introduction to Computer Architecture - Designing .www.oreilly.comWhat is Computer Architecture? - University of Washingtoncourses.cs.washington.eduRecommended to you b

Modelos de iPod/iPhone que pueden conectarse a esta unidad Made for iPod nano (1st generation) iPod nano (2nd generation) iPod nano (3rd generation) iPod nano (4th generation) iPod nano (5th generation) iPod with video iPod classic iPod touch (1st generation) iPod touch (2nd generation) Works with

NEW BMW 7 SERIES. DR. FRIEDRICH EICHINER MEMBER OF THE BOARD OF MANAGEMENT OF BMW AG, FINANCE. The sixth-generation BMW 7 Series. TRADITION. 5th generation 2008-2015 1st generation 1977-1986 2nd generation 1986-1994 3rd generation 1994-2001 4th generation 2001-2008 6th generation 2015. Six

The following iPod, iPod nano, iPod classic, iPod touch and iPhone devices can be used with this system. Made for. iPod touch (5th generation)*. iPod touch (4th generation). iPod touch (3rd generation). iPod touch (2nd generation). iPod touch (1st generation). iPod classic. iPod nano (7th generation)*. iPod nano (6th generation)*

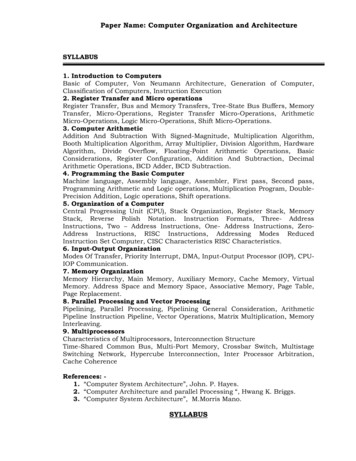

Paper Name: Computer Organization and Architecture SYLLABUS 1. Introduction to Computers Basic of Computer, Von Neumann Architecture, Generation of Computer, . “Computer System Architecture”, John. P. Hayes. 2. “Computer Architecture and parallel Processing “, Hwang K. Briggs. 3. “Computer System Architecture”, M.Morris Mano.

In Architecture Methodology, we discuss our choice for an architecture methodol-ogy, the Domain Specific Software Architecture (DSSA), and the DSSA approach to developing a system architecture. The next section, ASAC EA Domain Model (Architecture), includes the devel-opment process and the ASAC EA system architecture description. This section

12 Architecture, Interior Design & Landscape Architecture Enroll at uclaextension.edu or call (800) 825-9971 Architecture & Interior Design Architecture Prerequisite Foundation Level These courses provide fundamental knowledge and skills in the field of interior design. For more information on the Master of Interior Architecture

Business Architecture Information Architecture Application Architecture Technology Architecture Integration Architecture Security Architecture In order to develop a roadmap for implementing the DOSA, the current C-BRTA architecture was mapped onto various architectures in the form of heat maps.