Here’s How I Write–Hebrew: Psychometric Properties And .

Here’s How I Write–Hebrew: Psychometric Propertiesand Handwriting Self-Awareness Among SchoolchildrenWith and Without DysgraphiaSarina Goldstand, Debbie Gevir, Renana Yefet, Adina MaeirOBJECTIVE. This study investigated the psychometric properties of the Here’s How I Write–Hebrew(HHIW–HE) and compared handwriting self-awareness between children with and without dysgraphia.METHOD. Fifty-eight children (29 with and 29 without dysgraphia) completed the HHIW–HE. Occupationaltherapists provided corresponding ratings that were based on objective handwriting assessments. Selfawareness was measured through child–therapist consensus.RESULTS. The HHIW–HE has an internal consistency of a 5 .884. Children with dysgraphia ratedthemselves as significantly more impaired than controls on 6 of 24 HHIW–HE items and on the total score,with medium to large effect sizes (0.37–0.61). Mean child–therapist agreement was significantly higher forthe controls than for the research group, t(56) 5 4.268, p 5 .000.CONCLUSION. Results support the HHIW–HE’s validity. Children with dysgraphia reported morehandwriting difficulties than did controls; however, they tended to overestimate their handwriting abilities.Goldstand, S., Gevir, D., Yefet, R., & Maeir, A. (2018). Here’s How I Write–Hebrew: Psychometric properties andhandwriting self-awareness among schoolchildren with and without dysgraphia. American Journal of OccupationalTherapy, 72, 7205205060. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2018.024869Sarina Goldstand, MSc, OT, is Doctoral Candidate,Department of Occupational Therapy, University of Haifa,Haifa, Israel; sgoldstand@gmail.comDebbie Gevir, MSc, OT, is Occupational TherapySupervisor and Regional Advisor for Health Professions,Ministry of Education, Jerusalem, Israel, and Instructor,Department of Continuing Education, School ofOccupational Therapy, Faculty of Medicine, HebrewUniversity and Hadassah Medical Center, Jerusalem,Israel.Renana Yefet, MSc, OT, is Head OccupationalTherapist, Tzohar HaLev Special Education Schools,Ashdod, Israel.Adina Maeir, PhD, is Associate Professor and Chair,School of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Medicine,Hebrew University and Hadassah Medical Center,Jerusalem, Israel.Handwriting difficulties can have serious ramifications on children’s academicachievement, school participation, self-esteem, and overall well-being(Engel-Yegeret et al., 2009; Feder & Majnemer, 2007). The prevalence ofschoolchildren with dysgraphia is high, with estimates varying from 10% to30% (Cermak & Bissell, 2014; Karlsdottir & Stefansson, 2002). These childrenoften experience repeated failures, may perceive themselves as unable to improve their skills, and simply give up (Rosenblum et al., 2003). As a result, theymay develop an avoidance of writing, coupled with numerous negative academic and psychosocial consequences, such as getting poorer grades, beingmislabeled as lazy, and having reduced self-esteem (Weintraub et al., 2009).Therefore, it is not surprising that handwriting remediation is a common areaof pediatric occupational therapy practice (Giroux et al., 2012; Hoy et al.,2011).Client-Centered PracticeThe client-centered occupational therapy approach supports the active involvement of clients in the therapy process by considering their personal assessment of their abilities and encouraging their participation in selecting therapygoals (Hammell, 2013). The use of client-centered approaches and tools toenhance clients’ role in their care has been advocated by professionals in avariety of health care disciplines as a means of contributing to the effectivenessand quality of intervention outcomes (Verma et al., 2006). However, when theThe American Journal of Occupational TherapyDownloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 09/04/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms7205205060p1

client is a child, intervention goals are often prescribedby their occupational therapists, parents, caregivers, orteachers. This approach is problematic because goals established for children by others are much less motivatingthan those selected by children themselves (Josman &Rosenblum, 2011; Majnemer, 2011; Missiuna et al.,2006; Tatla, 2014). Hence, children with handwritingdifficulties are not always sufficiently engaged in the intervention process.Engagement in the intervention process encourageschildren to work, reflect, and talk about their learning atcognitive, affective, and operative levels (Woodward &Munns, 2003). Therefore, they feel more in control oftheir learning, have opportunities to direct their ownlearning process (Kobus et al., 2007), and become moreinvested in their occupational role as students. Fearingand colleagues (1997) described clients’ active engagement in identifying their problems and collaborating inintervention as a fundamental part of the client-centeredapproach. However, occupational therapists often find itdifficult to elicit self-appraisals and client-centered goalsfrom young clients (Pollock et al., 2010). Thus, tools thatfacilitate children’s self-assessment and goal setting mayelicit powerful and enduring levels of their engagement inthe learning environment (HaLevi, 2009; Missiuna et al.,2006; Schunk, 1985).Self-AwarenessSelf-awareness is an important component of metacognition that is positively linked to learning outcomes.Not only does it involve cognition, but it also interweavescognitive and affective components, including motivation, to stimulate effort and persistence toward fulfillingone’s goals in the face of obstacles (Efklides, 2009).Self-awareness of their strengths and limitations enablespeople to manage their difficulties by setting attainablegoals, monitoring their progress, and reflecting on theirincreasing effectiveness and achievements. This processelicits enhanced self-esteem and the motivation needed towork toward improving their skills (Zimmerman, 2002).Self-perception of one’s abilities may also foster the useof learning strategies, contributing to one’s efficacy instriving toward learning goals (Pajares, 2009).Comparing clients’ self-ratings with clinicians’ ratingsof their abilities or performance on objective performancemeasures is a commonly used method of assessing selfawareness in occupational therapy (Lahav et al., 2014).Disparity between self-ratings and ratings by others or testperformance is considered to be a measure of unawareness (Hoza et al., 2012). An instrument that can informoccupational therapy practitioners about children’s perceptions regarding their handwriting abilities would bevaluable in helping practitioners develop intervention approaches that are meaningful to their clients (Cermak &Bissell, 2014; Keller & Kielhofner, 2005). This type ofinstrument could also be used in research to expand theavailable body of knowledge on the awareness of childrenwith and without dysgraphia regarding their handwriting abilities. However, this component is often missing in formal handwriting assessments and intervention(Cermak & Bissell, 2014).Engel-Yeger and colleagues (2009) recognized theneed for and developed a self-report handwriting questionnaire (i.e., Children’s Questionnaire for HandwritingProficiency). They found that second- and third-gradechildren with proficient handwriting perceived theirwriting competence to be better than their peers withhandwriting difficulties. Josman and Rosenblum (2011)also developed a handwriting awareness questionnairefor children, adapted from the Contextual Memory Test(Toglia, 1993). They found that improvement in children’s handwriting awareness was related to improvementin their handwriting skills after intervention.Here’s How I Write–Hebrew (HHIW–HE; Goldstandet al., 2013), originally published as Kach Ani Kotev(Goldstand & Gevir, 2009, 2012), is an innovative pictorially based Hebrew-language self-assessment and goalsetting tool for children in Grades 2–5 created to promoteclient-centered intervention for schoolchildren withdysgraphia. A pilot study by HaLevi (2009) on theHHIW–HE was conducted, and the findings supportedits utility and feasibility. HaLevi also reported that thetool facilitated children’s engagement in the therapeuticprocess and reported it to be a “fun” process. Goldstandand colleagues (2013) developed and adapted an Englishlanguage version of the tool modeled after the originalHebrew-language tool. Both versions are designed to helpchildren identify their handwriting strengths and weaknesses and select treatment goals in a child-friendly andmotivating manner (Cermak & Bissell, 2014; Goldstand& Gevir, 2012). The content validity of the Englishversion was supported through an expert-validation process (i.e., all items achieved ³80% agreement amonghandwriting experts; see Ayre & Scally, 2014). Knowngroups validity was supported by the statistically significant differences found between the self-ratings of childrenwith proficient and poor handwriting (Cermak & Bissell,2014). The objectives of our study were to investigatethe psychometric properties of the HHIW–HE and tocompare the self-awareness of handwriting abilities between schoolchildren with and without dysgraphia.7205205060p2Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 09/04/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/termsSeptember/October 2018, Volume 72, Number 5

MethodParticipantsParticipants comprised a convenience sample of 58 Israelichildren in Grades 2–5 attending a mainstream educational program in central Israel. They included 44 boys(75.9%) and 14 girls (24.1%) between the ages of 7.1and 10.10 yr (mean [M] age 5 8.4 yr, standard deviation[SD] 5 0.87). Participants with dysgraphia were recruited by 10 pediatric occupational therapists experienced in handwriting intervention from their area ofresidence. The therapists evaluated the handwriting ofchildren referred to them by teachers or parents. Theyidentified 29 children with dysgraphia based on scores³15 on the Brief Assessment Tool for Handwriting(BATH; Lifshitz & Parush, 1999) and scores ³1 SDbelow the mean scores on the Hebrew HandwritingEvaluation (HHE; Erez & Parush, 1999), an objective,standardized Hebrew handwriting evaluation. The control group (n 5 29) was matched on age range andgender and determined to be proficient at handwriting(BATH scores below the cutoff [M 5 7.41, SD 5 3.17],and normative performance on the HHE) by the thirdauthor (Renana Yefet). Exclusion criteria for both groupswere significant neurological and primary sensory impairments or chronic diseases.InstrumentsThe BATH is a 16-item questionnaire designed by expertoccupational therapists to identify schoolchildren withhandwriting difficulties. It is completed by an occupationaltherapist familiar with the child or by the child’s teacher. Itencompasses aspects of handwriting function including legibility, the writing process and performance, andquestions targeting the emotional aspects of writing. Eachitem is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from0 (never) to 3 (always), with higher scores indicating poorerperformance. The total score ranges from 0 to 64, and thecutoff score for the existence of handwriting problems is15. The tool underwent an expert-validation process, andthe final items were selected based on ³80% agreementbetween 14 handwriting experts. Internal reliability is high(a 5 .9). The validation process included significantcorrelations between scores on the BATH and the HHE(r 5 .46–.65, p .01), and significant differences betweenthe scores of children with and without dysgraphia (n 5189), t(58) 5 20.78, p 5 .00, supporting its known-groupvalidity (Lifshitz & Parush, 1999).HHIW–HE is a pictorial self-assessment and goalsetting tool for children in Grades 2–5 designed to helpchildren evaluate their handwriting strengths and weaknesses and to determine, together with an occupationaltherapist, their handwriting intervention goals. The toolconsists of 24 item cards plus 1 demonstration card (i.e.,totaling 25 cards) and a goal-setting form. One side ofeach card contains a statement and matching picture depicting a child with proficiency regarding a certain aspectof handwriting. The card’s flip side contains a statementand a picture depicting a child with difficulty regarding thatsame aspect of handwriting (Figure 1). For each of the24 cards, the examiner shows the child both sides and thenasks the child, “Which is more like you?” The child responds by selecting a side (positive vs. negative handwritingattribute) and then qualifies his or her response as “all ofthe time” or “some of the time.” A negative handwritingattribute is scored as either 4 points (all of the time) or 3points (some of the time). A positive handwriting attributeis scored as either 2 points (some of the time) or 1 point (allof the time). The total scores range from 24 to 96, withlower total scores indicating more positive self-perceptionsof handwriting abilities than higher total scores.The HHIW–HE is administered after the child andtherapist have established a therapeutic relationship, thechild’s teacher reports on his or her perceptions of thechild’s handwriting, and a formal handwriting evaluationis administered. After the self-assessment stage of theHHIW–HE process, the therapist helps the child definehis or her treatment goals in a child-centered manner(Goldstand & Gevir, 2012).Content validity was supported by the results of anexpert-validation process involving nine experienced pediatricoccupational therapists with a minimum of 10 yr of expertisein handwriting intervention. The final items were selected onthe basis of 80%–90% agreement among the experts (Ayre& Scally, 2014). In a pilot study, HaLevi (2009) found75%–80% agreement between children’s responses on theHHIW–HE and therapist scores on the HHE (Erez &Parush, 1999) among 10 Israeli children (ages 7.5–10.3 yr,M 5 8.5) with handwriting difficulties attending a regulareducation program. These findings support the ability oftypical children in this age range to self-report on theirhandwriting ability. In addition, the HHIW–HE test–retestreliability was performed over a 2-wk interval with 14members of the control group and was been found to beacceptable (r 5 .65–1.00, p .05; Yefet, 2012).ProcedureAfter obtaining approval from the Hebrew Universityethics committee, the researchers contacted 10 pediatricoccupational therapists (³8 yr of experience) from central Israel to recruit participants for the research group.The American Journal of Occupational TherapyDownloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 09/04/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms7205205060p3

Figure 1. Sample cards from Here’s How I Write–Hebrew: A Child’s Self-Assessment of Handwriting and Goal Setting Tool.Note. Row 1 (from left to right): “I like to write” and “I do not like to write.” Row 2 (from left to right): “I hold the page with my other hand when I write” and “I donot hold the page with my other hand when I write.” From Kach Ani Kotev [Here’s How I Write–HE], by S. Goldstand and D. Gevir, Jerusalem: Authors. Copyright 2012 by the authors. Reprinted with permission.Control group participants were recruited with a snowball procedure and matched to the research group according to age range and gender. Consenting parents ofboth study groups signed an informed consent, and thechildren provided assent. The BATH and the HHE copytask were administered to the control group to confirmhandwriting proficiency, and the children were then ratedon the HHIW–HE items on the basis of the objectiveassessment results. The recruiting therapists identifiedchildren with dysgraphia based on the BATH and HHEscores. The third author (Renana Yefet) reviewed theadministration protocol delineated in the HHIW–HE7205205060p4Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 09/04/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/termsSeptember/October 2018, Volume 72, Number 5

manual (Goldstand & Gevir, 2009) with the therapists,after which they scored 21 of 24 of the HHIW–HE items(excluding 3 items relating to children’s feelings abouthandwriting, such as “I like to write”). Next, all participants completed the HHIW–HE, and the scores of theresearch and control groups were compared to determinethe tool’s known-group validity.Data AnalysesStatistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSSStatistics (Version 19; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Giventhe non-normal distribution of the HHIW–HE scores,nonparametric statistical analyses were conducted. Independent samples Mann–Whitney U test was used tocompare the total score and the 24 item scores of theHHIW–HE between the study groups; the Bonferronicorrection for multiple comparisons was then used (p 5.05 for the 24 cards). Internal consistency was computedusing Cronbach’s a. Nonparametric effect size r wascomputed for between-group comparisons (Fritz et al.,2012).The construct of self-awareness was operationallydefined as the percentage of child–therapist agreementin HHIW–HE ratings. Each rating was first categorizeddichotomously; that is, items scored as 4 (always) or 3(some of the time), reflecting negative perceptions, werecategorized as negative statements, whereas items scoredas 2 (some of the time) or 1 (all of the time), reflectingpositive perceptions, were grouped as positive statements. If both the child’s and the therapist’s ratingswere in the positive or negative statement category,agreement was surmised. Items that children ratedpositively and that the therapist rated negatively werecategorized as overrated by the child, and in the opposite condition, as underrated by the child. Spearman’s correlations were computed to examine thecorrelation between the children’s and the therapists’ratings on the HHIW–HE items and between thetherapist’s scores on the BATH and the child’s HHIW–HE total scores. The percentage of child–therapist agreement on the tool’s items between the groups was comparedusing t tests.ResultsThe children in the research group scored in the dysgraphic range on the BATH (16–32; M 5 22.69, SD 53.91), whereas children in the control group receivedscores indicating no dysgraphia (1–14; M 5 7.41, SD 53.17). Internal consistency, determined using Cronbach’sa for all 24 items, was good (a 5 .884), and removal ofany of the items was not found to substantially change thesize of the coefficient (range 5 .875–.884). For knowngroup comparisons, the calculation of between-groupHHIW–HE scores revealed that children with dysgraphiarated themselves as significantly more impaired thanchildren without dysgraphia on the total HHIW–HWscores and on 6 of the 24 items. Analysis of group differences in self-ratings revealed moderate to large effectsizes (Table 1).For between-group child–therapist agreement anddisagreement (i.e., self-awareness), the mean percentageof items that children and therapists agreed on was significantly higher for the control group (M 5 84.88, SD 510.72) than for the research group (M 5 71.25, SD 513.43), as confirmed by an independent sample t test,t(56) 5 4.268, p 5 .000. However, when comparing thepercentage of disagreement between child and therapist,Table 2 shows a clear pattern whereby overrating wasfar more frequent among children with dysgraphia thanamong the controls. In addition, a significant moderatecorrelation was found between the total HHIW–HE andtotal BATH scores of the control group (r 5 .457, p 5.013), whereas no significant correlation was found in theresearch group (r 5 .171, p 5 .374).DiscussionThe current study was performed to examine the psychometric properties of a new client-centered handwritingself-assessment tool for schoolchildren in Grades 2–5. Thetool was also used to examine the degree of handwritingskill self-awareness among children with and withoutdysgraphia.Psychometric PropertiesData analysis of the tool revealed a Cronbach’s a of .884,indicating that the tool’s items are related to each otherand support its internal consistency. Significant differences were found between the groups on the totalHHIW–HE scores, with moderate to large effect sizes,reflecting the tool’s abil

handwriting difficulties than did controls; however, they tended to overestimate their handwriting abilities. Goldstand, S., Gevir, D., Yefet, R., & Maeir, A. (2018). Here’s How I Write–Hebrew: Psychometric properties and handwriting self-awareness among schoolchildren with and without dysgraphia. American Journal of Occupational

Texts of Wow Rosh Hashana II 5780 - Congregation Shearith Israel, Atlanta Georgia Wow ׳ג ׳א:׳א תישארב (א) ׃ץרֶָֽאָּהָּ תאֵֵ֥וְּ םִימִַׁ֖שַָּה תאֵֵ֥ םיקִִ֑לֹאֱ ארָָּ֣ Îָּ תישִִׁ֖ארֵ Îְּ(ב) חַורְָּ֣ו ם

Independent Personal Pronouns Personal Pronouns in Hebrew Person, Gender, Number Singular Person, Gender, Number Plural 3ms (he, it) א ִוה 3mp (they) Sֵה ,הַָּ֫ ֵה 3fs (she, it) א O ה 3fp (they) Uֵה , הַָּ֫ ֵה 2ms (you) הָּ תַא2mp (you all) Sֶּ תַא 2fs (you) ְ תַא 2fp (you

Biology Paper 1 Higher Tier Tuesday 14 May 2019 Pearson Edexcel Level 1/Level 2 GCSE (9–1) 2 *P56432A0228* DO NO T WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NO T WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NO T WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NO T WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NO T WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NO T WRITE IN THIS AREA Answer ALL questions. Write your answers in the spaces provided. Some questions must be answered with a cross in a box . If .

2 *P56432A0228* DO NO T WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NO T WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NO T WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NO T WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NO T WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NO T WRITE IN THIS AREA Answer ALL questions. Write your answers in the spaces provided

6 Write 5/10 in its simplest form 7 Write 16/28 in its simplest form 8 Write 8/16 in its simplest form 9 Write 6/12 in its simplest form 10 Simplify 6/10 Day 6 Q Question Answer 1 Simplify 2/14 2 Simplify 3/12 3 Write 40/80 in its simplest form 4 Write 72/81 in its simplest form 5 Write 5/25 in its

Crush It - Cart Card. Crush It - Cart Card with Club Name. PRINT. Cart Cards. Place these in your carts during prime sign up seasons. Contact us today! 000.000.0000 name.here@clubcorp.com. Introducing a Golf Program for Life. Copy here copy here copy here copy here copy here copy here co

MD5(Pre_master_Secret SHA(‘CCC’ pre_master_secret clientHello.random ServerHello.random)) Generation of cryptographic parameters Client write MAC secret, a server write MAC secret, a client write key, a server write key, a client write IV, and a server write IV Generated by hashing master secret

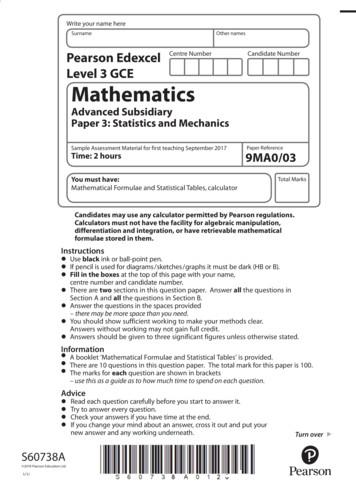

Pearson Edexcel Level 3 GCE Turn over *S54258A0221* DO NOT WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NOT WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NOT WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NOT WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NOT WRITE IN THIS AREA DO NOT WRITE IN THIS AREA SECTION A: STATISTICS Answer